FEBRUARY 10th 2025

BLOODY ENGINES… ROCK GARDENS TO MOROTO, NORTHERN UGANDA

As well as discovering a real love of the small children, this journey is notable for the amount of work that’s been required on my ageing motorbike, now 17 years old. It HAS had a hard life since I bought it seven years ago, with 45,000 miles on the clock. It’s done 25,000 more varied miles, on all sorts of terrain from smooth Chinese tarmac to appalling rutted, bumpy, sometimes risky mountain goat tracks.

I’m riding into northern Uganda, going to the desert town of Moroto, remote, and home to the Karamajong people, colourful tribes with a bit of the feeling of ‘old Africa’. Out in the country, I see the lithe young women sporting their swinging, flared, multicoloured pleated skirts – above the knee, and men draped in coloured cloths, wearing the most bizarre headwear: crocheted hats like something Chaplin used to wear for laughs; tall, ringed with bright colours of wool, sort of bowlers crossed with top hats, with small upturned rims, often surmounted by a big feather – an ostrich for the fortunate.

****

As I ride north from Sipi, the engine starts to stutter. I put it down to the blustery wind. I’m really not sure if I’ve another problem with my engine, perhaps as a result of all the bodging repairs done over past weeks? I remember that ‘Karachi’ will be in Moroto. He’ll help if required. Five years ago, by odd coincidence to the very day, he supplied a new front tyre for the Mosquito.

I treat myself to the pleasant Mount Moroto Hotel, £18 for a room opening onto the large garden, and a view of Mount Moroto beyond the french window, chuckling at how my travelling life has changed since my all-time accommodation lows in Coatzacoalcos, Mexico, and Yusekova, Turkey, many years ago. Moroto’s a hot, pleasant town, calm and clean, probably thanks to the army presence.

Next morning, I buy a new front tyre from Karachi and set off to investigate the mountain range that borders northern Kenya. I bounce along uncomfortably, the new tyre is rather harder than the old one. It isn’t long before I begin to ask myself what I’m doing. I’m riding on uncomfortable, dusty tracks in hot sun to go to look for a view that might not even be there! What am I proving? That I can do it? Well, I know I CAN do it, but do I WANT to? What will be my reward? Why am I bothering? That’s the trouble with lone journeys: all the soul searching and personality analysis.

Then my decision is made for me. The engine starts running unevenly again. This time it’s not the wind, it’s as if it has dirty petrol. Could be, I think: I was forced to purchase that Coke bottle of fuel in Sipi. I’ve a reason to turn round. I ride back to Moroto, and ‘Karachi’.

****

I sit in hot sun outside the workshop, watching Francis, a mechanic who gives me confidence, try to identify the problem. He appears methodical, disciplined and efficient – rare qualities. He’s worked for Ali for nine years. Ali, AKA ‘Karachi’, a Pakistani motorcycle dealer here in remote Moroto, came from Pakistan in 2002, opening a business in Kampala. Somehow, he ended up with this up-country offshoot in the deepest north, supplying the large army garrison in town.

Francis strips and services the carburettor. It takes most of the rest of the hot day. In the evening I take it for a fast test ride but it still coughs and stutters. Back I come on day two for further adjustment. Another test ride. After 30 kilometres the machine dies, fortunately just two kilometres from Karachi’s workshop. Francis rides to the rescue. Immediately – and rather impressively – he goes straight to the source of the problem: rough, twisted connections by Kato, the Kapchorwa mechanic, who hasn’t got a roll of insulating tape!

I ride the bike 20 kilometres round town in case it stops again, but it feels like my old Mosquito at last. Now I have to decide which way I’m going, north to hot remote mechanical uncertainty or back south to green mountains and family?

I think the decision is contained in the semantics of the question.

****

To go back a bit… On January 28th, I rode back round the mountain to Uganda. I’d spent a few relaxed, enjoyable days in Kitale with Adelight and the children, and Wanda and Jörg, now old friends from Köln, who keep a camping car in Tanzania and, like me, travel to escape European winters. They are cheerful, curious and kind people who’ve made many friends in Africa.

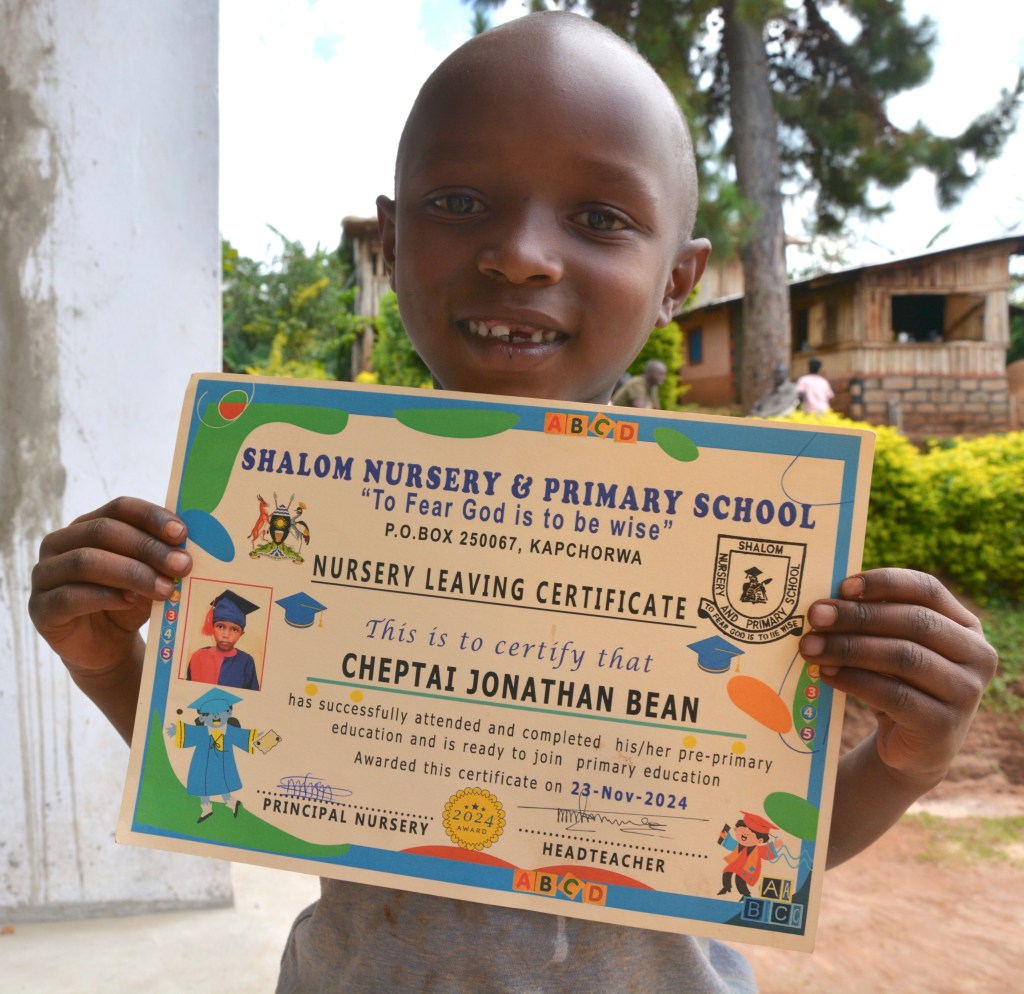

Ugandan schools would start the school year on the 3rd of February, after a nine week holiday. I wanted to spend the last of the holiday with Keilah and Jonathan. I rode back.

The standard of Ugandan education is dreadful. I’m tempted to say that it’s a policy of the dictatorship to keep their vast population (49% below 14 years) in ignorance: it makes for easier control. In rural districts a minority attend school. Government schools are lamentable, while private schools operate as a business (many of the better ones mysteriously owned by government officials…)

My mission, having accepted the education of my two ‘grandchildren’, was to find a better school for them. They’ve been at a boarding school in Kapchorwa, 10 miles from home: boarding being a choice forced upon us by the lack of safety of the school transport, with 50 or more young children packed in a minibus on the dangerous mountain road. Last year, an exhausted driver from their school caused an accident that killed a family on a boda-boda. The school paid off the police and relatives to avoid bad publicity. At that point, in disgust, Alex and I made the decision that Keilah and Jonathan should board at school. Their attainments suffered, the food was negligibly poor, they often had to share beds with older pupils in search of owners’ profits and Jonathan was sometimes sick and losing weight. Precious had many arguments with the administrators, to no avail.

Alex’s brother, Cedric, whom I like a lot, told us of Tower Primary School in Mbale, 30 miles down the mountains. Cedric, as a computer technician, runs the school’s gadgets and knows the staff. We went to inspect – and were impressed, instantly enrolling the children for the year about to begin. The school’s not cheap, almost certainly owned by someone in government, as is everything of quality in this utterly corrupt regime; it was rated seventeenth in the country in the recent academic year.

The children will live in basic dormitories, each overseen by apparently kindly matrons. They will eat not very interesting food: mainly carbohydrate and oily stew, little meat or vegetable, and very few luxuries, unless supplied by parents. It’s a hard life – but Keilah and Jonathan are wildly excited by the news that they are to go to a big school in the city, which boasts a (rather small) swimming pool! Their delight knows no bounds. In the evening, after I pay £250 for registration and uniforms, they dance about my room, climbing all over me exclaiming at their new clothes and wondering at the coloured pictures on the school’s 2025 calendar, thrilled by the swimming pool!

Next comes shopping for the long list of requirements. Alex takes the cost of that, another £250-plus from his guest house income. I transfer the £500 to cover the term’s fees for the two gleeful children. Half a day is spent sorting and packing new tin trunks with copious amounts of toilet paper, kilos of soaps, no less than FIVE KILOS of sugar each (with, happily, four tubes of toothpaste and a toothbrush!), pens, pencils, bedding, books, paper, buckets and basins. The children dance and exclaim in delight. They LOVE school, and this is an adventure.

Reporting time is 07.00 on Monday the 3rd. It takes a hired car to transport all the mattresses, buckets, bedding, blankets, basins and trunks – and two ecstatic children and their parents. I wisely stay in bed. I’m missed on the journey down, Alex tells me later, “Oh, I wish Uncle Jonathan was driving us!”, says Keilah, but I’m soon forgotten in the excitement of arrival. “There were BIG people there!” exclaims Precious proudly, “The parking was FULL! Big cars! Rich people. A lot of fat children!”

Soon Keilah and Jonathan dismissed their mother – Alex was at the bank paying the fees. “We have to go to class with our friends!” And away they ran, to their new adventure.

I’m delighted that my sponsorship of these two lovely, lively small people will provide a secure future for at least two African children, and ease the burden from Alex, a man of great integrity, who would struggle to see his children do so well. They are bright sparks, Keilah and Jonathan, now with a lot of exposure to so many mzungus. With the correct direction they can go far. I tell Keilah, who told me she wanted to be a nurse, that she, “can be a doctor, a surgeon, anything you want! Don’t ever let anyone tell you otherwise. You are equal to those boys.”

****

The children safely at school, the compound quiet, it’s time to continue my travels. BUT, the Mosquito isn’t working. Now it won’t start. Back it goes to Kato, the mechanic in Kapchorwa. It needs a new rectifier, he says. Kato always appears honest and decent, but he never tells me a price, getting me to look up the European price for parts and telling me that ‘original’ parts are expensive in Uganda. I wonder if he does deal with his suppliers? I’ve no way of knowing, and no one in this cash economy has heard of receipts. But what am I to do? He may not be Africa’s best mechanic, but he’s the best I’ve found (except in remote Moroto, a 200 kilometre ride into the sticks). I am dependent upon him. I have a trusting nature, judging others by my own standards, but when he says he paid £90 for the rectifier, that in the Netherlands costs €86, I begin to wonder. Am I paying the mzungu price? Is it an original item from Japan? I have no way of proving anything and must just trust him, I suppose.

After lunch on the third day he roars into the compound at Rock Gardens. “Your bike is good, very good!” It sounds good, and he sounds confident. “I took it to the Yamaha mechanics in Mbale (the Mosquito is a Suzuki) and they told me the rectifier wasn’t matching the control unit we replaced so it was not charging the battery. Now with the new part – original! – it’s good, very good!” Apparently, the mismatch was frying the cables in the charging circuit. I hope he’s right as it’s cost me another £120… Keeping the Mosquito running this year has already cost me £750.

The tacho tells me Kato’s ridden 230 kilometres. It reads 384 since I last filled the tank. “I’ve never seen it so high on one tank of fuel! There must be just a smell left!” He likes to ride my bike.

“No, it will be very OK!”

We get him a boda-boda to take him back to Kapchorwa. It’s too late for me to ride north now, it’s already 3.00. I’m desperate to leave Rock Gardens. Desperate.

****

On the 2nd, Enoch died 100 yards down the lane past Rock Gardens. I remember Enoch, a cheerful child who looked about seven when I photographed him a few years ago. Alex reckons he might have been fifteen or sixteen when he died a couple of days ago. “They are small, they don’t grow with sickle cell disease. They don’t live past teenage.” So poor Enoch had a short spell and is now gone. I’m sorry of course. But death here means ersatz ‘culture’ intervenes, this godawful travesty of ‘tradition’. The new habit began just a few years ago: amplified pop music throughout nights until burial. A truck weighed down with speakers the size of capacious wardrobes pulls in to the bereaved compound. It’s big business, along with the rented gazebos and Chinese plastic chairs.

Now, after a night of pounding, unimaginative ‘music’ from gigantic loudspeakers 100 yards away, in this ghastly, disrespectful exhibit of local ‘culture’, I am determined to leave. But it’s too late. It’s after 3.00. I’m condemned to another night, tossing and turning with earplugs pushed tight, that can’t shut out the ‘thump, thump, THUMP, thump, thump, THUMP, thump, thump, THUMP, thump, thump, THUMP, thump, thump, THUMP, thump, thump…’ I can shut out the ‘music’ but not the sub-bass vibrations.

This is not culture or tradition, it’s just amplified noise pollution of no relevance whatsoever to a funeral, that’s become a habit. It provides excuses for morally bankrupt locals to get drunk and attracts disruptive youths and idlers. “But if you don’t have this music, no one will come,” protests Alex’s father. But who wants these elements at the memorial of their dead son?

Tradition used to be wailing, and in much of Africa, drumming. Then came amplification, generators and sub-bass speakers that vibrate for kilometres, and music made not by musicians but technicians and toneless singers (shouters) who rely on mechanical repetition for effect. So tradition sinks to exploitative commercialism.

And of course, it all costs a lot of money that poor rural villagers don’t have. Wood butcher Tom is part of the burial committee, being of the same clan. The estimates for burial are around three million Uganda shillings: £600+. No one in this community has that sort of money. Neighbours must chip in. Crooked politicians will come and harangue the mourners and use campaign funds to buy votes. The average manual worker gets about £4.50 a day, and most here don’t work anyway. Think of the school fees that money could pay.

Alex and I had planned a long hike for tomorrow, but he can’t go now. It would be an insult for him to leave for a walk while the burial is going on. And people in this poorly educated, jealous, conservative village take offence on a whim. So I’ll ride north instead.

After another noisy night.

When I DO leave, the petrol runs out 500 yards from Rock Gardens! Fortunately, I can freewheel downhill to Sipi centre and buy a Coke bottle of petrol, probably pinched out of someone’s tank. It’s JUST enough to reach a petrol station in Kapchorwa.

Bloody Kato, I think, as I fill up the entire tank.

****

Leaving at last after the second disturbed night, I go to the ATM in Kapchorwa for cash. Somehow, Kato and Alex have eaten my previous £225, and I’m heading into remote areas. I’ve determined on a ride into Karamoja, the northern tribal regions of Uganda that border South Sudan. There’s a short cut that drops steeply down the mountainsides into the scorching plains far below. It’s bumpy and very dusty, with vistas of central Uganda fading in the misty distance. I’ve been told there’s now a tar road all the way to Moroto when I reach the valley floor. But somewhere after a few miles, I take a wrong turn and end up with 30 miles of disgusting earth and stone, smothered in red dust that infiltrates every nook and cranny of the bike, me and my bags. It’s disgusting, and the scenery is not attractive.

It’s my second attempt at investigating the tribal north. Five years ago, I turned round in the face of relentless mud and rain clouds. I struggled north through craters and ponds of clay mud, blathered and filthy, tired and wondering what the hell I was proving.

And, oddly enough, it’s much the same now… Maybe Moroto is my travelling nemesis! A place I reach, and wonder why. I go through the same soul-searching for 48 hours. Admittedly, a malfunctioning motorbike in these remote regions does focus my thoughts. Perhaps too, the vast and unleavened landscape doesn’t help. It’s scrubby bushland: dry, stunted trees – almost none of which reach maturity as everyone here depends on firewood and charcoal for domestic needs and rural cash sales – and spiky, sketchy growth spread over dull grey brown earth. The scenery is uninspiring. Very uninspiring. Just scrubby dry lands backed by ranges of blue mountains and the bland blue of the huge desert sky.

****

It’s the people I’ve come to see, I suppose: these left-behind vestiges of an old Africa of colonial era encyclopaedias. These days though, I know much of this is just a facade: imposed by poverty, not culture. The colourful clothes are certainly for real, and the people often friendly, but I get edgy about the ethics of passing by and gawping, as Tourism booms in such places. It’s the only way to encourage any economy here, to bring in hard cash: exploit the curious ways of indigenous peoples… Tourism is becoming ugly as it’s now the richest business for so many African countries. The money falls overwhelmingly into the pockets of corrupt politicians and fat businessmen, not filtering down to rural communities who provide the ‘colour’. We come, we look, we take a selfie, we post our ‘exotic adventures’ on Instagram.

But do we really learn much about what we are looking at..?

****

Sometimes I ride through small towns and remote villages, past isolated dwellings, and wonder what it must be like to LIVE here, and in all likelihood, know nothing else but a stick and thatch hut in a vast flat expanse of bush land, with few trees that reach any size before they are culled for firewood and charcoal burning? No shade from the searchlight sun. Most here don’t go to school, and learn nothing of any wider life than this circumscribed poverty and drought, both physical and intellectual. Boys tend the family cows and goats; girls carry heavy containers of water and head-loads of firewood and become pregnant in early teens. Women have average six children, risking death in childbirth many times over, doing all the household and farming chores, and slaving over smoking sticks to make some sort of food for their multitudes of children dressed in rags and their useless men – who do nothing.

The landscape is denuded and dull, parched in the fiery equatorial sun. Knowledge, and perhaps curiosity, is limited to the immediate surrounding, augmented perhaps by tinny basic phones, the only possession for most. If accident or ill health intervene it’s ‘God’s will’ and just your bad luck. You probably die, or become crippled and beg. This is the reality of life in much of rural Africa. No comfort, a terrible diet of carbohydrate and starch, little stimulation – balancing on the knife edge of existence. It’s no romantic ideal of the ‘simple life’, just lifelong hardship little better than that of the desiccated animals ranging this dry scrub and desert. Experiencing all this changes my appreciation of the privileges of the life I lead. Unless devoid of compassion, you can’t ride through this without a certain horror that THIS is how most of the world lives, not with the comforts we take so much for granted.

And with a very deep gratitude that I am one of the lucky ones.

****

It’s more fun, I realise, to indulge in the warmth of my families. They too add a sense of the exotic as I get inside their lives, but with a reality and depth that is rewarding. Anyhow, after most of two days sitting outside the workshop of Ali Karachi, I’m not entirely trusting my Mosquito any more. Do I really want to venture into the remoter north, or will I be more confident riding back towards family, help and some good hiking with my companions for now? Probably.

I think I’ll cut and run again from Moroto. Back to the green mountains. And family.

****

Spotting that my Ugandan bike insurance has run out I find that Moroto has just one agent. I’m now insured by the Catholic church, the richest organisation in the world. What power they have! One of the major Ugandan banks is also Catholic church owned – the Centenary Bank. Some pray, all pay, that’s the reality of Catholicism. Peddling hope and platitudes while the peasants pay, and faith leaders cosy up to the dictators to keep the people subservient… Cynical? You bet I am! I’ve seen a lot of these countries.

Cheerful Juliet, with an itchy hair weave that requires poking with a ballpoint at regular intervals, renews my annual insurance for £11, typing the document, one-fingered, on an old Olympia manual typewriter with a dicky ribbon, a machine I haven’t seen outside a museum display for four decades. Well, the Catholics don’t waste their astronomical wealth.

“Insured by the Pope!” exclaims Alex as Precious laughs at my story later.

****

Then I’m on my way south again. The sun hammers down out here in this vast burned expanse. I can’t escape it. There’s no ‘in-the-shade’ temperature on a motorbike. I leave Moroto behind, beating down the tar road with big views on both sides: scrubby growth dotted with pimples of ancient volcanic plugs, sometime backed by hazy, jagged mountains. But it’s too empty; and if it’s empty here, what the heck is the rural north like? With company I’d probably have gone on, on my own perhaps my discretion is wise: up there, the roads are dirt, and I don’t really trust the engine yet, although it does FEEL more like my old Mosquito after Francis’s care and attention.

People walk the roadside, sometimes a nod of acknowledgement of my wave, but these are reserved people. They have no discernible destination, loose-limbed, tanned black by the relentless UV from the big star overhead. It’s an African mystery. Where are they all going, miles from anywhere? A constant feature of this wonderful, strange continent.

Even on the endless valley floor, most of the time I am higher than Ben Nevis. We forget how high so much of these east African countries is.

Baked to a crust, after about three hours I take the short cut again, steeply and rockily up the side of the mountains to Kapchorwa. In six or seven of the ten miles I battle up two and a half thousand feet. Serious trail riding; great exercise and good for flexibility as I dance on my footpegs over rocks and dirt. The bike enjoys the cooling air; it’s funny, I can FEEL the difference, as if it’s grateful for the coolness of the altitude. I am too. And it’s green again up here.

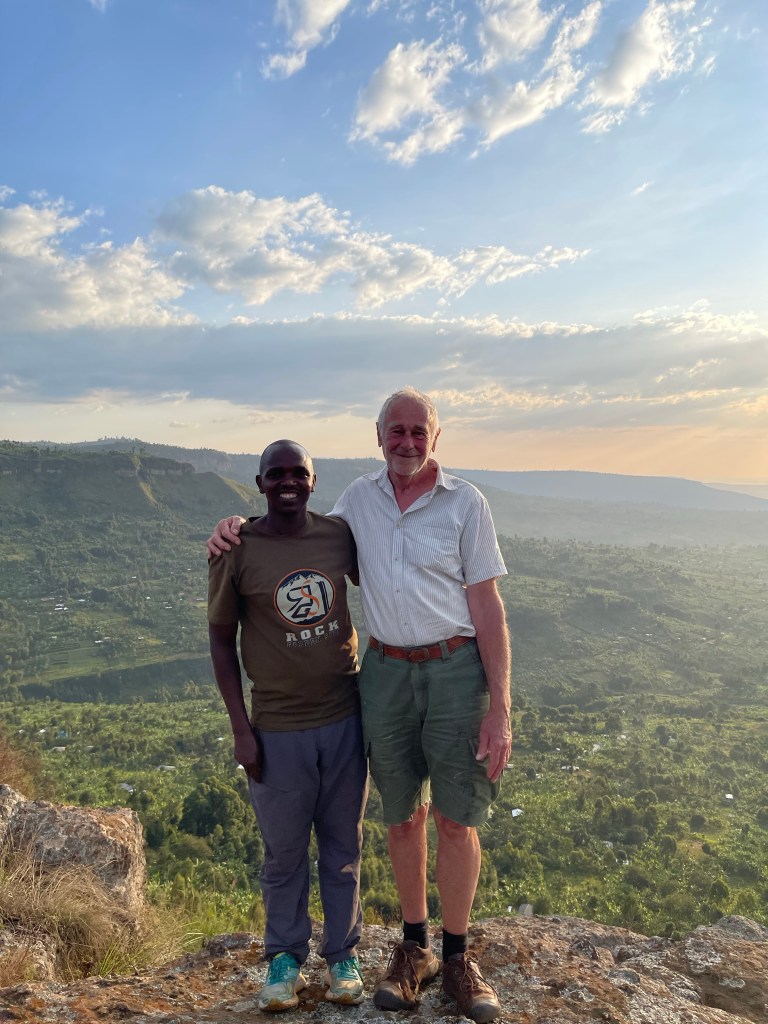

Back at Rock Gardens, I am warmly greeted by all. Alex now has a small staff. Celestine is a sort of deputy manager; Shiela and Marion do the chores, and Eric works with the guests as guide and messenger. It’s bringing some efficiency, and Precious is better tempered now she has relief. It’s still difficult, running a popular guest house with no electricity, and currently no water. We DO have a better three quarters of a mile of gravel road from the centre of the village, but in grading that, they broke the water pipes! There’s no planning in Uganda. It’s been a week now – of carrying hundreds of jerrycans from the spring. It’s been going on so long that Alex now hires a group of boda-bodas to lug the water up the hill. More loss of profits.

There are always guests now; they’ve started sending one another – the best marketing, I tell Alex. They love the welcome, the atmosphere and the ‘traditional’ rooms – that I’ve invented! There’s just one left to decorate now before I leave in March.

Last week, Rock Gardens got its second award from the multinational giant booking company. “You can call yourself ‘Award Winning’ now,” I say. “Getting a Traveller Review Award two years running is not bad!” Best in Sipi, and probably in the region. He’s quietly proud of achieving his dream, is Alex. So am I. I never expected this success. But Alex has an attribute rare in Africa: he plans ahead. He’s canny too. As we walk locally, he shows me that he is quietly purchasing bits of land, four plots so far. He’s respected by his clan chiefs and does honest but smart deals with them, spreading the costs of the land over time, so they get an income, and he slowly gets the land.

Land is wealth in Africa. “Anything can change here. When this president dies, he intends his son to take over, but there are generals who object. Who knows, there could be civil war again. Businesses will suffer, but people will always need food. Land will always have value, especially with our high birth rate and belief that sons must own land…”

He’s already using the plots to grow potatoes and matoke, and planning far ahead to planting trees. Smart man, thinking ahead. I’m so happy that all my instincts proved so accurate. He’s a fond friend now too. And I a father figure to advise and guide, and an intercontinental scenery designer whose skills have helped his business become a real success story.

Funny how things turn out.

****