EPISODE TWO – JANUARY 14th 2026

I’m often struck by just how remarkable all this is. Here I am riding a high precipitous rock and gravel road along the very lip of the Great African Rift Valley, inches from a great plunge into the oven-hot depths. I started trail riding forty eight years ago – but then it was for fun, brief Yorkshire trails over boggy moors and up and down stony tracks. Here, it’s sometimes the only road to use. But, I admit, it’s usually the one I choose, even if there’s a tarred alternative.

Riding along, bumping and bucketing about on one of the most impressive trails I can imagine, people run to the roadside to stare and wave; crowds of schoolchildren cheer at me, a flutter of pink palms and white smiles on young black faces, skin so smooth, unlined yet by the hard lives most of them approach, here on this escarpment slope. They’ll scratch at the red soil and herd a couple of cows and some goats, until they end up creased and dressed in tattered clothes like the old crone with one eye on the back of a boda I stop to ask directions from the rider. She looks at me like something from another planet – about her age, in all likelihood, but a world apart, a result of an easy life in the profligate North, good nutrition, education, medical intervention when required, relative wealth and CHOICES – the biggest difference between the prison of poverty and my relative ease of life. I’m choosing to ride this stunning track; she has to, bumping about on the back of a small motorbike in such discomfort for an old woman. Time was, of course, she’d have had to walk this way, without even the pennies for the ride. The ride is perhaps a luxury conferred by her old age.

It does make me reflect on the inequalities I witness everywhere around me and puts life in a different perspective. No one here, in their late seventies, in any condition – of wealth or health – can CHOOSE to do what I’m doing. Even if they wanted to.

****

Thirty kilometres on this punishing red road bulldozed across the steep slopes and I get lost. But there’re always boda-boda riders to flag down and ask the way. They make a living – of sorts – riding their unmaintained small Chinese machines on these vague roads. I follow this rider for several kilometres, breathing in his cloud of dust. My eyes are prickling, despite goggles; I think I’m suffering a paucity of vitamin A. My diet here is pretty simple, although mangoes, of which I have about five kilos (for £1!) bouncing on the back of the bike, contain it. It’s mainly in liver, fish, cheese, butter, squashes and greens – none of which feature much in the African diet. Lack of vitamin A, I found from a clever Ghanaian doctor years ago, is a cause of much blindness in Africa, as the surface of the cornea becomes dried and crazed. Feels like mine’s going that way these past weeks, with itchy eyes. Again, my knowledge and wealth mean I can get some supplements from a pharmacy tomorrow.

He puts me back on my road and I twist and turn on the high Cheringani Highway once again. It’s a fabulous road – tarred, this one, for now at least, depending on maintenance. It clambers through high scenery, hills rolling off into the blue midday, the sky deep blue above. I’m always conscious of the sheer immensity of African skies. As I ride up to 3060 metres (10,000 feet) above sea level, I dodge cows and sheep; people wear woolly hats and coats up here, and I must stop to put on a jumper under my jacket. Surprising how cold 15 degrees can feel!

There’s a road I’ve never taken, that drops sharply over the southwest face of the hills to the straggly town of Kapcherop, where tea bushes carpet the slopes around town. From Kapcherop, I’ll sweep on down, on deteriorating tar, full of dangerous holes and speed humps, the obsession of Kenyan road engineers, to the Kitale road. I was told of this road last year by some fellows in a tea house. I’ll try it…

Never again! It’s an APPALLING loose rocky staircase slithering downwards. I must concentrate and leap and dance about on my little bike. TEN MILES of this punishment. Good exercise, I tell myself. But I’m aware too, that a small mistake can cost me dearly. I mend much slower now. However, I stay upright and my Mosquito, now running soundly, does good work. We eventually emerge onto tar again – both of us worse for wear.

Then, with speed humps, wandering cattle, mad boda riders, straining vastly overloaded lorries with bits flapping, potholes and grumbling tractors almost as wide as the road with dry maize stalks, it’s the usual African riding back to base at Kitale.

****

For four days, I went to Kessup to hike in and around the Rift Valley with William, the friend I made nine years ago. ‘The goodness is…”, as he so often says, is that we both like people and we both enjoy walking.

Three or four years ago, I gave William a Holstein cow. He called her Dutch. The best way for me to help my friends in Africa is to encourage financial independence. The cow cost £375. A year on, she gave birth to British, a male calf. Another year later, last October, she gave birth to Joy (named after my mother!). A few days ago, while we were hiking into the great valley, Dutch was bellowing all day, a sign that she was ready to be ‘served’, in the coy, apparently sexist, phrase. William, in great excitement, called the vet who specialises in artificial insemination. He guarantees a female calf – or money back (£40). William dreams of Wilhelmina to complete his dairy farm. With three milking cows, and the sale of British, the male, his dairy will be complete. I’ve also paid for a rough wood shelter, and to bring water pipes down the mountain to his shamba. About £750 of my money can make William self-sufficient, able to sell milk to the cooperative for a few pence a litre and feed his cattle on homegrown maize.

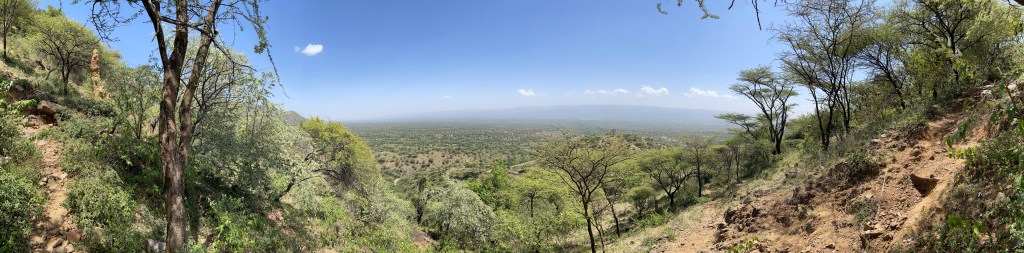

In return, William introduces me to his community on the edge of the Kerio Valley. ‘William’s Mzungu’ is well known on the red dust tracks and amongst the fertile shambas below the soaring cliffs that top the Rift Valley here. Each day, we hike in the fine nationally protected forests on top of the escarpment or down through fertile smallholdings into the burning depths. The bottom of the valley, where the finest mangoes in the world grow, is 2750 feet lower than the guesthouse where I stay; the top of the cliffs are another 1250 feet above. That’s 4000 feet from bottom to top! All on friable rocky, stony informal footpaths in the hot sun. Eleven mile, five mile and eight mile hikes, staggering up and down these step paths at between 3900 feet at the bottom and 7750 altitude at the top. Mighty exercise.

The forest on top of the escarpment is magnificent and silent, filled with birdsong and dappled light. A still day, the shadows merely flicker and dapple the bright undergrowth. A few cows graze, with bells tinkling. Deep blue acanthus blooms in spiky leaves. The sky above is crystal blue, unblemished.

Then the great chasm of the arm of the great African Rift Valley appears through the trees far below. So dramatic, this vast plummeting 4000 foot deep natural cleft. Just now, it’s filled with haze and the other face, twelve or fifteen miles away, to which I once unforgettably hiked through vicious thorn bushes and between grazing giant elephants, is invisible.

****

Desmond, an intelligent 27 year old I’ve met in past years, joined us on the walk up to the top to drink moratina, a home brewed, brilliant yellow honey wine, brewed on Sundays. The government has imposed tax and restrictions on its sale, but this being Africa, there are ways around things. It’s just less visible.

Apparently, I influenced Desmond to ‘get his life together’ a few years ago, with advice to take charge of himself, stop wasting time at home as the last born of nine, and go out and face the world. I have NO recollection of any such sage advice, but it’s remarkable where a mzungu’s influence lands! An onerous responsibility.

One day, Desmond stopped behaving like a teenager, upped and left home. He did menial work in a city hundreds of miles away, renting a room for £30 a month, but determinedly paying his rent on time. His landlord was impressed, and happening to be an official in a far distant education authority, he offered Desmond, trained as a teacher, a post. It’s in an end-of-the-world town, in the farthest corner of Kenya, sandwiched between war-torn Somalia, and troubled Ethiopia. You can’t go further east or north in the country, than this place that ends as an arrow head of Kenya, with two war-torn countries actually visible on either side. I suspect Desmond got the job because no one else wanted it. It’s a tough area of Islamic fundamentalism, where life is cheap. He will be authorised as a fully fledged junior school teacher in a few months, launched on a career without the bribery usually necessary.

To buy a teaching job, the going rate of bribe in Kenya is about £2900. To enter the military, expect to buy your job for £5750 at least. It’s for this reason that everyone is propositioning the mzungu to buy their land in Uganda, where these bribes are correspondingly enormous. Selling land that has passed through generations of peasant farmers and which can never be rebought; capital that is irreplaceable. Better to get your son (seldom daughters, of course) a paid job in some form of government work, than be a farmer – despite these being some of the most fertile regions of Africa. Government jobs bring the bribes and backhanders and the only potential to make you rich – if you have no ethics and only the morality assimilated from your leaders.

Chirpy, optimistic Desmond is committed to his post. He reckons to stay for five years, in a prejudiced Moslem area where Christian Kenyans aren’t popular, there’s no alcohol and no women. His ambition is to earn enough to start farming back here in the Kerio Valley area. He deserves to make it, this fellow with good integrity, admirable moral concepts and determination. But he’s made a hard choice – or perhaps, as so often in Africa, he HAD no choice.

****

Some of Desmond’s pupils, aged as little a 12 or 13, are married already. And those are the fortunate ones: allowed an education by their fathers. FGM, officially illegal in Kenya, is still practiced in remote corners of the country and women have so little status. Many die, too young for childbirth. Only education has any chance of changing habits and opinions in Africa – and even then, the majority of educated men retain their sexist, misogynistic, homophobic, superior attitudes. (Look for a feature film called NAWI, made in Kenya recently and entered for the 2026 Best Foreign Film Oscar – a powerful film).

At breakfast, a week ago in Uganda, a tiny girl came selling bananas from a tray on her head. A shy smiling child, she looked about six, surely too young to be trading, even in Sipi? But Shiela said she was nine. Precious thought she might indeed be nine years old. “There are five following her. I don’t think she’s reported [for school]; she takes care of the younger ones. The mother is just… huh…”

What chance has a child like this? Condemned from birth to poverty and probably a mother by fifteen herself. A baby machine for life. ‘Tradition’.

Alex and I came upon a couple of lads wasting their time. With election fever hotting up in Uganda, Alex quizzed them about a female candidate campaigning for their rural district.

“Huh! We don’t want to be controlled by women!” exclaimed the older boy. “Women are for marrying!”

There’s little hope for change in Africa. The boy is 16 years old. All over the continent women do ALL the work, despised by men. To most men, they are little more than baby machines and slaves. “Lower than donkeys, then?” I ask. My audiences laugh at what they see as my joke, but they don’t argue.

Changing habits and attitudes in Africa is painfully slow, if at all. “It’s the way we do it here. It’s tradition…” The excuse for every bad practice all over the continent.

****

Tomorrow, I’m going back to Uganda. Just in time for the ‘election’ on Thursday, not that there’s ever been any doubt of the winner. It’s just a costly exercise to show there’s ‘democracy’. I’m told that the internet has been turned off by the ruling power, so I’m writing in sunny Kitale this morning instead.

Oh, I forgot to say. Adelight GOT PAID! For the contract signed off before the end of March last year. They government has retained a significant sum for six months as a guarantee, in case ‘anything goes wrong’ – with a job satisfactorily completed already eight months ago…

But she’s singing this morning as she mops the floors!