Maria – an ever-cheerful child

DAYS 58-63. SUNDAY 23rd – THURSDAY 27th FEBRUARY 2020. KITALE. KENYA

Lots of things different on this journey, even my diary writing. Not my daily discipline, but written in batches as activity dictates.

And activity didn’t change a lot this week! A pleasant, homely time with my Kenyan family, who accept me as part of their extended family. I’ve so often written that the most admirable single element of life all over Africa is its continued adherence to the extended family system. Blood relations mean less than proximity and an ability to adapt to one another. Here am I, from another culture completely, accepted as a brother and uncle figure to these fine people, some of whom are themselves not related by blood. In the West, we put so much emphasis on that close blood relation, defining our families, dividing our wealth and possessions, our loyalty and support in much narrower confines. Some of the ‘sisters’ in this household are indeed Adelight’s direct sisters, but frequently there are other young women and girls around. They have no actual blood line in common, sometimes even arising from other tribal roots, but they act as much sisters as any nuclear family. Rico’s flexible family is a unit to be admired, as is he, for his commitment to these girls and young women, brought up at his own considerable personal sacrifice of money and comfort, but to his greatest satisfaction in his large and lovingly warm family who look on him as their father.

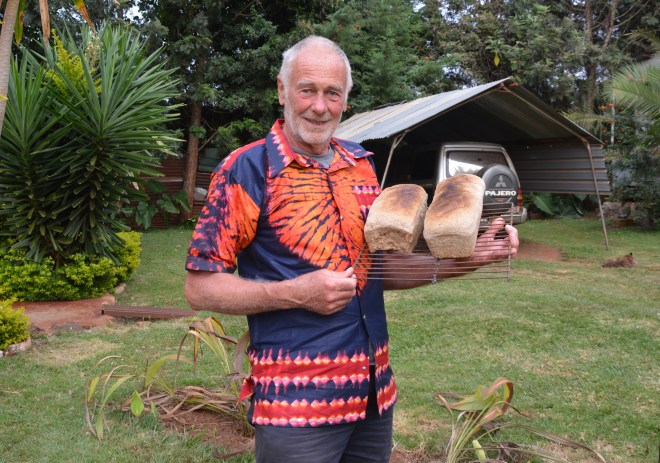

It’s been amusing this week to give Adelight some bread lessons. She told me that she’d been trying to make her own bread but had produced only bricks. I diagnosed flour with insufficient gluten and went with her to peruse the available selection. Somewhat nervously, I made bread one afternoon – the very afternoon I had elected to provide the wherewithal for a family barbecue party before I left. Thankfully, my baking impressed. A second batch the next day confirmed my ability! The Joy Bean bread technique has now a foothold on the continent of Africa! She’d be happy to know that.

Joy Bean’s bread recipe reaches Kenya

On Sunday, from Kessup I headed back by the Cheringani Highway again to Kitale – the newly tarred and magnificent road that now sweeps through fine scenery, where once I bounced and struggled on the dusty track that wound its way over these magnificent hills – and, truth be told, I loved much more. I knew it is always quite chilly in those hills, formerly kept at bay by the exertions of the bumpy road, but now the empty, smooth tar road takes little physical effort and the chill is apparent. I looked up the road on the map and find that it climbs as high as 2900-plus metres (nine and a half thousand feet). At that altitude, even on the Equator, you need some exercise to keep warm. It’s a glorious ride, huge views down to the north on the latter part and extensive vistas over plunging valleys and forested mountainsides elsewhere. Small villages scatter along the roadside, rough places of earth and rusty iron sheeting. The farmlands are green and fresh, the clouds scudding high in the blue dome above. It’s good to be alive on such a ride. And good to be on a motorbike, out in the freshness, experiencing the changes of temperature, the scents of the forests, the occasional scattering of light raindrops from the high, unseasonal slate clouds that drift past above; to wave at the surprised populous and the calling children; weaving my way between errant donkeys and goats and matted sheep with Rasta dreadlocks from mud and shit. Birds, some of them spectacularly sequinned flashes of iridescent feathers, others large lazily floating raptors, their eyes peeled onto the ground below for vermin and carrion, soar and wheel about on the wind. Joyful yellow sunflower-like bushes line the roads, happy against the red earth embankments. The road winds and rolls over the glorious hills. People wave. I am happy and content, riding along at often no more than 25mph, stringing out the pleasures. These Kenyan highlands are some of the finest scenery in Africa.

So back to Kitale and family warmth and a few final days of organising the last part of the 2020 safari and preparing the bike and belongings to be stored in Kitale until my promised return next Christmas. Uncle Jonan (Maria’s delightful diminutive for me) is now a fixture! And next year maybe I’ll be less restricted by ridiculous leg injuries and be more fully active. Precious and Alex want to take me to stay with her parents, in the far western part of Uganda (the part I have admired most) on an island on the very scenic, large Lake Bunyoni, one of the beauties of Uganda.

Family barbecue

By the time I return, delightful little Maria, a bundle of ever cheerful energy and charm, with her idiosyncratic three year old chatter, will have grown to be a four year old. She’s been a highlight of my stay. I’ll miss the family unit. It’s been easy. Adelight said one day that I felt like a brother, and we certainly enjoy one another’s company. I’ve the patience to actually enjoy going shopping with her! In the evenings we are Scrabble opponents, a game at which she quite often beats me, a testament to her intellect, since she is playing in her second language against a native speaker with a large vocabulary. Marion and Scovia brighten our days and the other various girls who come and go, do so with a cheerful positivity and joie de vivre that is engaging. I hope I can be part of this happy family again in nine or ten months’ time.

Well, that’s all in the future. ‘Who knows tomorrow?’ they ask in Ghana. Who indeed? Still, good to have future ambitions!

My Kenyan family says goodbye at Kitale airstrip

…AND SO TO SOUTH AFRICA…

DAY 64. FRIDAY FEBRUARY 28th 2020. JOHANNESBURG. SOUTH AFRICA

Culture shock can be just as disorienting within this continent as coming from Europe to Africa. In a matter of four hours I am in a totally different African atmosphere. I’m in a cheap hotel rather close to the end of the Oliver Tambo International Airport runway in Johannesburg. Of course, this is not a new experience. I’ve been here in Johannesburg at least a dozen times. But it’s the first time I flew in from another part of Africa. It’ll be interesting to see how it measures up. It’s also going to be different in that I have no motorbike in this country at present.

I’d been considering the possibility of a ‘two centre’ trip this year for some time. Then the restrictions of my Achille’s tendon injury, the reduction in realistically feasible bike miles, the fact that back in April I came down here as a ‘consultant’ on a new museum project, and then the happy coincidence of Kenya Airways emailing me as a ‘valued client’ about their special 40th birthday offers, all coerced me into purchasing this ticket and travelling on down to the bottom of my favourite continent. If I’d booked my flight when I first considered the idea, it would have cost me £523. By the happy chance of that email a few days later, my ticket cost £414. Considering I got my return flights from Bristol to Nairobi for the grand sum if £1.46 (see day one), it seemed a lucky opportunity. Here I am in South Africa.

Up early and a prompt breakfast (homemade bread) and a short ride to Kitale airstrip, with the whole family to see me off. An hour’s flight to Nairobi airfield and the inevitable taxi negotiation to the main international airport. Few airports in Africa are accessible by any means of public transport. The rapid transit railway DOES actually reach the Johannesburg international airport these days, but the fare is £9 from the nearest station. It’s £8 from much further away by taxi. It smacks of efficient lobbying by the taxi companies! Fred, a friendly driver, conveyed me from the Nairobi airfield busy with small aircraft to the anonymity of the vast airport. Gladly, I have my frequent flyer lounge access that makes flying such a much more pleasant experience.

We landed into pouring rain – there was over 12mm, half an inch, of rain forecast for Johannesburg today – and a second taxi (in one day! This is NOT JB travel!) to a cheap hotel in a wasteland of car dealerships and garages. But at £15 in South Africa’s most populous city, it’ll do for the night.

As darkness fell, I walked out to seek supper. I am in Kempton Park, by the looks of it, a fairly run down suburb of this huge city, of which most travellers are fearful or at least apprehensive. I had to walk a mile or so, on broken pavements on this rainy night. Coming from another part of this wonderful, absorbing continent, I suddenly realised, as I walked the scruffy streets amidst noise, people and incessant activity, that I wasn’t in the least nervous. How well I remember my first visits to this country, when everywhere I went people – almost exclusively white people – enumerated all the things I shouldn’t do and all the things of which I should be frightened. The word used was always the perfidious ‘they’, the threatening ‘others’ – aka black people. I’ve just spent two months amongst black-skinned people. My friends. In fact, I spend a quarter of every year now as the conspicuous ‘other’, the odd man out. I have completely stopped seeing people as black-skinned. It’s odd, I just see ‘people’.

Walking through the wet streets, I thought to myself that most of my white acquaintance here would be having kittens to see where I was! It was noisy and boisterous. And very human. It was extravagant and natural. A few youths called out, not taunting, just perhaps surprised, rather loud greetings. Much more brazen than in East Africa, but not unfriendly or disrespectful. They hung about outside ‘bottle shops’, noisy, bumptious youths. I even entered a ‘bottle shop’ to buy myself a couple of long-missed Castle Milk Stouts.

Assuredly, I wouldn’t walk down those dimly lit streets late at night with my camera over my shoulder, or my pocket bulging with money. But then I wouldn’t do that in Leeds, Plymouth – Totnes, for god’s sake, any more. I felt no threat whatsoever. It’s all in the mind. And when you look frightened, you are the most vulnerable.

I remember my first visit. 2002. My Elephant was stuck in a crate, bobbing around in a cargo ship outside Durban harbour, beleaguered in a dock strike. My poor motorbike, in a crate, inaccessible. The dock strike lasted three weeks. Though I had friends to generously host me, neither they nor I had expected that hiatus. So I took off on buses to see a bit of South Africa while I waited. I rode south and on the first night of my short solo tour, I ended up in the coastal town of East London. It’s a large regional town and something of a black seaside resort. I found a hotel, of sorts. My room had a balcony (!). I leaned on the railing looking down towards the sea and over the streets. I didn’t dare to adventure into town.

I stood for half an hour looking out. It was just a pleasant seaside sort of city, the usual restaurants and cafes visible, the Indian Ocean tossing along the shore. Suddenly, and I can remember this now as I write, I thought to myself, ‘What are you afraid of? Think of the very dodgy places you’ve travelled all over the world! The backsides of Asian and Latin American cities, in the cheapest hotels known to man!’ The roughest villages in the Hindu Kush, the Andes, North Africa, Middle East you name it, I’d seen the seamy sides of those places. I’d travelled on the most impecunious budgets in the toughest, roughest places. And here I was, in semi-westernised South Africa, in a pleasant seaside city – a sort of Yarmouth or Cleethorpes of the southern hemisphere, and I was AFRAID?

I was afraid because every white person I had met in the previous two weeks had insisted I should be afraid! Stuffing my valuables under the bed, I walked out with a few pounds in my pocket and a smile on my face. I walked confidently down the centre of the pavement, greeting people (rather surprised people, it must be said) and smiling broadly. From that day – to this, walking through a run down black suburb of the ‘evil’, ‘dangerous’ city of Johannesburg – I have had NOT ONE moment of apprehension in all the time I have spent in South Africa! And I have spent months here all told, riding my motorbikes through townships, cities, villages and remote countryside. And I’ve come to enjoy the place and I respond to noisy youths with a big smile and a raised thumb. They love it! An old white-bearded bloke giving as good as he gets from them. It’s all they want. They are so unused to it.

It’s not so frequently that people smile at me here in South Africa. There’s always this distance, this suspicion, this inferred inequality. I don’t feel that in Kenya or Uganda. There, we’re equal. My fast food supper was served by a pretty young woman. She reacted to MY smile so happily. I felt I had scored a victory. I had made a young black South African woman respond with the attractive warmth of her smile. It’s not something that you witness often in this strange, unhappy land. I have to work harder for smiles here.

Most people around me now are lighter complexioned than in East Africa, and they do things with a certain bravado and lack of respect or modesty. It’s noisy, brash, flashy, more competitive, a trifle more aggressive. Faces are ‘deader’, less expressive, less eager to engage. Eyes look away, they don’t return my smile. It’s more like being at home than in Africa, where everyone loves to talk. There’s a wall, a barrier, a doubt, reluctance. A slowness to smile, to laugh, to make human contact.

I’d forgotten the South African propensity for kitsch and sentimentality – and for trying to hide paucity of taste and luxury by adding numerous silly pillows to the beds. Pillows that then have to be stored somewhere when I actually get into said bed – the usual place being flung in a corner, where I fall over them if I get out of bed in the night. This rather basic, ostentatiously unpretentious hotel has pillows everywhere to try to disguise the utilitarian furnishings and the camouflage-green emulsioned walls. Two of the pillows have the silliest text imaginable: ‘wifi + food + my bed = perfection’. Those two stupid pillows had an extra energetic trajectory into the corner of this militarily green room.

This is a land of appalling fast foods, with attendant obesity problems, often exaggerated in black races, as with African Americans. The South African diet has to be one of the least healthy in the world. Those with money eat red meat and starch, those without eat dire junk food – fat, salt, sugar. South Africa appears to take all its foodie influences from USA… The queues for McDonalds go round the block… There’s KFC, Chicken Shack, McDonalds, Wendy’s, Debonair Pizza, Burger King, all the rest. Hardly a scrap of food I want to put in my mouth!

DAY 65. SATURDAY FEBRUARY 29th 2020. HARRISBURG. SOUTH AFRICA

So, the choice was Kentucky Fried Shite or an Afrikaans rugby bar at the back of a petrol station. In the interests of travel experiences, the latter won hands down.

I think…

This is a country that brings out all the prejudices in me, all the ones I pretend I don’t have, with my extreme exposure to the world in all its glories. This is a country, the only one in Africa, this astonishing continent, that makes me conscious of my skin colour. It’s a country that confuses me as much as did Japan – the country I still sum up, when asked, by: ‘I had preconceptions when I arrived. When I left, even those were wrong!’

Anyway, I chose the smoky (yeah, this is South Africa) Afrikaans bar across the road from the deadbeat Grand National Hotel, in which I have stayed on my motorbike journeys on several occasions, Harrismith being a convenient staging post to and from Lesotho and my friends in Durban and Bloemfontein. It’s a tired sort of town, dating back to colonial times and Harry Smith, who founded the place. There’s a bizarre war memorial with an obviously English soldier bowing over his rifle in respect to the fallen of World War One; another commemorates those who fell ‘in the service of South Africa’, in the Boer War. I could find no memorial to the many thousands of black African soldiers and support staff slaughtered in the causes of those foreign wars. There are odd colonial overtones, utterly at odds with the brashness of this tired African town. I wandered into the town centre, such as it is, and found the end of a street market, noisy, incredibly littered, with an undisciplined, down at heel atmosphere that, on one hand I rather enjoyed but could also be read as pretty deeply depressing or threatening. This is a town down on its luck. In fact, it probably never had a lot of luck. It’s here perhaps as a junction on highways. Maybe it always was. The major toll highway from Durban to Bloemfontein and south to Cape Town passes by. Much of South Africa passes by. It’s a backwater going increasingly stagnant. The old colonial Grand National Hotel echoes the turgidity of the town. Electric security gates on the doors. Worn cord carpeting, scuffed furnishings, metal framed windows, empty corridors and a sense that life has passed by. Without taking much notice.

There are bottle shops everywhere and a lot of drinking going on, exacerbated by the end of the month pay day. Men are gathered noisily around the bottle shop doorways, getting drunk. Empty and broken bottles litter the streets: the usual African problem of low employment and lack of self discipline. Rico blames African mothers. He explains how they treat male children in a completely different manner to their daughters, cosseting the male babies, spoiling them, respecting them and teaching them to believe themselves to be more worthy than their sisters, the also-rans of Africa. It’s deep set prejudice, centuries of male privilege. And it manifests itself here on a Saturday afternoon like this. Men drink; women work. A few drunks lie already in doorways and the wide main street, Warden Street, resounds to the noise of young male revellers in cars with short exhausts and huge boombox speakers. There’s considerable drink driving around poor, forgotten South African towns like Harrismith. My solution to many – most – of Africa’s ills remains the same: put the women in charge and ban the production or sale of all alcohol over 4%ABV.

While the men drink away their meagre salaries and ruin their health, the women sell or shop, filling a million plastic carrier bags (South Africa hasn’t banned bags like Kenya) with groceries, often the products in the most lurid packaging, as if there’s a siege coming.

I had forgotten it was the end of the month. A mistake worth avoiding in South Africa. People are paid at the end of the month and ATMs have lines round the block. By good fortune, I had just enough cash from last April’s visit to tide me to Harrismith. Most Africans live hand to mouth and here, where the infrastructure is developed and people paid automatically into bank accounts, the end of the month is an important time. It fills the shops to capacity. Families shop as if the stores will be closed for the next month – as for many, without further economic support for four weeks, they will. All I wanted was a plug adaptor… It took 15 minutes at the tills to pay my £1.50. The hotel is aged enough to utilise the old three round pin 15 amp sockets that were once the norm in South Africa – and still are in backwaters like Harrismith.

Harrisburg and its peeling hotel suits my budget at £15, and it’s convenient to meet Michael, my old Durban friend, who is on his way to the national park nearby tomorrow. It’s also a stop on the long distance bus route from Johannesburg.

This Afrikaans bar shakes to the volume of rugby on multiple TV screens. This is a sport played by 90% white men, watched by almost all white South Africans. Soccer, meanwhile, is a game played by increasingly numerous very good black players; a game adored by every black African I ever met. The game that roars about this bar: “AAAAAHHHH! Kick the fucking BALL, you stupid oke!” yells a mountainous Afrikaner with pendulous flesh that is difficult to appoint to any known physiological map. He rises from his bar stool in necessarily slow motion; folds of flesh slumping knee-wards by gravity. He wears sloppy grey track suit shorts dangling about his knees. His Xtra Large tee shirt hangs like old theatre curtains from the cantilever of his vast wobbly stomach. While I have been here, he has downed three one litre bottles of Black Label lager. He must be three times my girth, with a long white beard. He scratches his crotch and waddles to the gents. Pasty faced, vastly obese, coarse, tattooed, probably horribly prejudiced about most of his neighbours…

And yet… He welcomes me warmly, as do those around the bar. Of course, my prejudices (that I don’t think I have) ponder whether they’d make the same welcome if the outer half millimetre layer of my body was black.

This is the ugliest nation on earth. You see, I said I have to accept that I too have prejudices! Fat, immensely fat, gigantically, waddlingly fat, pasty faced, unhealthy, bad skin, covered in tattoos. Or sharp featured, pasty faced, unhealthy and bad tempered like the witch who accused me of sitting in her seat on the bus. Happily, I had an upstairs seat at the front of the bus and a view of the wet road. At Vereening, up came a sour-faced Afrikaans woman of very acid demeanour, insisting that I was sitting in her seat. “It’s disgusting, I paid for this seat! It’s MY seat. I have seat 5A!”

“Yes, and this is seat 5B!” I pointed out reasonably. But she was so bad tempered she wasn’t listening. All the young (black) men around me pointed out that the alphabet generally held to a norm of A-B-C-D, but her anger was burning. The young man in the window seat – seat 5A – should have been sitting in seat 16D, down the back somewhere. I explained to him, but he seemed to have some sort of learning difficulty or perhaps he’d burned his brains on something earlier today. I pointed out to the screeching woman that I was in the seat assigned to me. Other neighbours spoke to the man in seat 5A in his own language but he either didn’t comprehend or wasn’t bothered. The Afrikaans woman fumed and spat behind me. “It’s disgusting!” she harrumphed. “It’s MY seat! Quite disgusting! You’re in my seat.” But I wasn’t. She’d picked her argument with the wrong passenger. She should have been railing at the (black) passenger next to me. Maybe I read more into her disgust at me, a fellow white passenger, not him? I stayed put and replaced my headphones. One thing Africa has taught me is that argument and bad temper solve no problems at all. Politeness is natural for most in this continent.

Looking for non meat food in South Africa is a generally pointless task. Especially in an Afrikaans sports bar. I ordered lamb curry. “What’s skilpadjies?” I asked the overweight Afrikaners at the bar as I searched the menu in vain for the vegetarian option.

“It’s liver,” replied my neighbour in a friendly manner. “Coated in… In…” He dried up as he tried to think what the coating might be in English. “Hey,” he called to one of the bar women, “you speak English. What’s XXXX? (I cannot begin to write whatever the word was).” The bar began to discuss how to describe the filth in which the liver might be coated. “Well, it’s like haggis…” said one. “No, it’s a sort of bacon!” said another. They compromised that it was liver wrapped in something unspeakable from a lamb’s intestine. “Oh! I think I have eaten it!” I exclaimed, remembering the time I attended an Afrikaans motorbike rally (!!) with Steven. I made the mistake once, and ate what I can only politely call ‘fat on a stick’. It’s one of the most repulsive things I ever ate (and that’s a pretty long list). “Yes, it’s VERY good! Good food,” said my immensely overweight, tracksuit shorts friend at the end of the bar, scratching his crotch again. “You should try it!” Hmmmm.

At the back of this bar is a small room. It’s lined with ‘slots’ – slot machines, one-armed bandits. It’s glittering with flashy lights and incessant visual interference. Six addicted gamblers – black – sit, glassy eyed with fatigue and tedium, unable to stop… They are the only black customers in the bar.

At the corner table sit a band of middle aged people. Smoking heavily. Bad skin. Beer guts. Tattoos. Three women, four men. Huge beer bottles in front of them. Bike helmets on the table between us. Their bikes are outside, fat, slobbish motorbikes that make a lot of noise and probably go fast, but don’t really go far and certainly never leave smooth tarmac. I’d put £100 on the fact they’ve never been to nearby Lesotho, best biking country in the world. Afrikaans people don’t go there, despite the fact it’s usually less than 70 miles away. Actually, I’d safely wager ten time that! One of the women is getting up to go. She’s pulling on a jacket and leather waistcoat. Free State bikers all belong to clubs. They have big embroidered badges emblazoned across their jacket backs. This dumpy lady has badges all over her waistcoat. Most are in Afrikaans. The only one I can read in English boasts the recommendation, ‘100% bitch’. I wouldn’t tempt fate that far, if I were her.

Afrikaners tend to hug a lot. Men and women. Imagine, if you can, two large rubber exercise balls trying to hug one another. You’ll see what I am seeing as I write!

So, you see, all my prejudice comes out here! Is it my age and conditioning? I grew into my political awareness at a time that we believed that apartheid was one of the biggest evils in the world of the sixties (as it was). Am I projecting that onto these people? These people who are at the same time immensely friendly and often generous too? I suppose we all see the world through our own filters. Mine are predisposed to sympathise now with indigenous black African people, from whom I have received more love and generosity than anyone else. Perhaps my prism is skewed here? Yet these people too, after 300 years or more, are indigenous African people. Just another colour and tribe. Another race. Yet they’ve fought alongside black Africans for their freedom. They qualify as African as much as anyone.

So why are they in their own bar? Separate, in this ‘rainbow nation’ that’s supposedly been united for 25 years?

The lamb curry wasn’t bad, however. But I had to resort to the jar of pickle to find some vegetable. I am in Afrikaans South Africa, where chicken is considered a vegetable!

What of the rest of my day, before I sat here with my three Castle Milk Stouts? (Small bottles!).

It was a half hour walk from last night’s cheap hotel to the efficient, relatively expensive rapid transit railway that brings the population – those that can afford the luxury – into the centre of Johannesburg. The rest (mainly black) go by minibus. The line is speedy, the distance surprisingly long, past mining exploits (gold is the reason for Johannesburg’s existence) and sprawling suburbs with a dotty pox of satellite dish disease, separated by wide greenswards and green-fringed motorways. The train deposits me into the heart of this seething city and to the main bus transit hub. “Do take care! Everyone wants to rob you here,” warned one kindly paranoid white woman as I stepped from the train. I felt no threat whatsoever, beyond normal city centre watchfulness in a rather run down area round the bus stations.

The road south from Johannesburg is through South Africa’s most boring landscapes. This is a huge area of gently undulating grasslands and farmland, split by occasional motorways. It rolls on and on, and then on. I recollect interminable tedious bike journeys here in the Gauteng region. From Harrismith the scenery becomes more stimulating. I’m approaching the magnificent Drakensburg Mountains that hold wonderful Lesotho so far up into the sky, where the range is called the Maluti Mountains. It’s Lesotho that has brought me back to the foot of this extraordinary continent.

“Oh, you’ve put the prices up!” I told Rose, the receptionist, as she processed my £15.38 on my credit card. “I hope you’ve repainted the rooms since I was here four years ago!”

“Noooo, I don’t think so…” she pondered with chuckle.

Correctly.

Golden Gate National Park. The view over my beer glass.

DAY 66. SUNDAY MARCH 1st 2020. GOLDEN GATE NATIONAL PARK. SOUTH AFRICA

Perhaps my greatest stimulation in travelling is not knowing what tomorrow will bring. Tonight I am staying in the middle of the Golden Gate Park in the Drakensburg Mountains, close to the new museum building being constructed in the valley below, a museum about the dinosaurs who roamed this area a couple of hundred million years ago. A museum on which I acted as a consultant (at last! It took me until I am 70! Haha) on a trip to South Africa last April.

My friend Mike is a facilitator of projects, mainly in museum conception now. He works out of Durban but we’ve known one another for many years, originally through his wife, Yvonne, long long ago my neighbour in the flat above mine in Ilkley, Yorkshire. They’ve lived in South Africa for over 30 years, and been my hosts and base for five motorbike trips. The fact that Mike and I work in the same field is coincidental, but fortuitous for me as it now provides a few days (unpaid) consultancy with my peers, in another culture. We’re here with Kath, researcher and writer for the project, for some creative meetings tomorrow and Tuesday.

We’d arranged to meet in Harrismith at 1.30. They have to drive within ten kilometres of the town to travel from Durban to the museum site and the well equipped national park campsite and the chalet in which I find myself tonight. I’ve a room with a view of the very scenic mountain ranges, curving walls of red and yellow rock rising in bluffs to oddly mushroom-like tops across the narrow defile. I’ve ridden here before, but never understood the geology and significance of the fossil beds that abound. It’s a geologically remarkable area, thick ancient mud layers topped ancient sand dunes, then topped and burned and pressed by volcanic waste. The rocks contain a plethora of fossils of great interest and amazing preservation. Fifty years ago a palaeontologist discovered a rich seam of dinosaur fossils marking the birthplace of thousands of dinosaur eggs. The great prize of the region is a fossilised egg, complete with hatching tiny dinosaur. The artefact is only palm sized, but of extraordinary detail – enough that the park service is spending millions to build a museum and interpretation centre in the valley below the discovery site. Of course, there could be hundreds more fossilised hatchlings in that ancient mudstone layer.

Harrismith is not a place to be stranded on a Sunday. “Where can I get breakfast?” I asked the Grand National receptionist about 9.00 this morning. She pondered my strange request for a moment. “There’s KFC and Wendy’s.” I consider neither of those purveyors of food. I spent a couple of hours criss-crossing the decrepit town, but sure enough there was no place open with so much as a cup of coffee. I was forced to purchase items in a supermarket to make my own scratch breakfast, eaten without cutlery or crockery. It was also impossible to find a single place to sit, until the same Afrikaans bar of last night opened its doors late morning and provided a bench for the final hour if my wait. Not so much as a public bench in town…

“This used to be a thriving town,” said Mike as we drove away, swinging down litter-strewn streets of decrepitude. “It was a centre for the Free State agricultural life. Now the citizens have taken over their own repair of roads and infrastructure from the municipality as it’s so inefficient.” I’d noticed that the town had very little civic pride and diagnosed that there was probably very little civic money either. It’s a sad place, thickly littered and scruffy. Residential streets lined with torn bin liners, from which vermin and birds have scavenged food scraps, and ditches and roadsides strewn with fast food packaging and plastic bottles. Afrikaans residents live behind electric fencing, spiked railings, razor wire, security bars and signs emblazoned with warnings of armed response from security companies. It’s grim. These are a people buttoned up, separate, enclosed, barricaded from the world around them, embattled in their own country. Why, even the churches, on just about every corner, are segregated – black churches and white churches. Could there be a greater contrast? Friendly, loose limbed, freewheeling East Africa to the Orange Free State in 36 hours?

I’d repaired to the Afrikaans bar by about noon. I don’t often take beer at lunchtime any more, but really, what else was there to do? I’d hiked three or four miles about this faded town looking for little more than a public bench, to no avail. At least there was a table on the pavement outside the bar. Mike and Kath rolled up about one, and we set off to drive another hour or so into the mountains. High above me now, the mountains hold up Lesotho. Later, touring some of the local sites that Mike wanted to show me – the rocks where the eggs were found, and that still contain many more clutches, a ridge of dinosaur bones visible in the mud layer, the fossilised sand ripples of an ancient dune – we ran into four cheerful dumpy Basotho young women. Seeing their smiles, their delight and excitement of a day out together by car, I realised how much I have missed Lesotho these past four years. These girls came not from Lesotho itself, but from one of the three South African Basotho tribes, each with their own royal family, some of whom we are here to meet tomorrow. These tribal offshoots live in the high regions of the Free State here on the edges of Lesotho and the mountain range.

My idiosyncratic ‘career’ has brought me many treats, not least the ability to work on four continents. I am content to be in the Drakensburg Mountains tonight, learning some ancient Basotho lore and a bit about the origins of diverse dinosaurs. I didn’t expect THAT a couple of days ago.

200 million year old dinosaur vertebrae

It’s cold and silent. Around me stand the silhouettes of the jagged dragons’ mountains, guarding the bones of legions of dinosaurs huge and tiny. I’m happy for a radiator in my room. It’s also drying my washing – for I have travelled perhaps the lightest yet to be here. One small backpack about two thirds full. It weighs less than seven kilos and will suffice for the next three and a half weeks. I can put my luggage on my back and just go whenever and wherever I want. I relish that freedom!

The view from over my breakfast coffee cup

DAY 67. MONDAY MARCH 2nd 2020. GOLDEN GATE NATIONAL PARK. SOUTH AFRICA

I do have – and appreciate – a lot of good fortune in life. For nothing more than any advice and ideas I might have for this team, I have two days accommodation and food and drink in this fine national park. I’ve paid for that with a few (informed, I suppose) opinions on museum design and concepts, and perhaps three new design ideas. I can swan in, sound wise and clever, and swan away again without the least responsibility. I don’t have to carry out those apparently clever ideas, only to suggest them and retreat. That’s consultancy for you! Haha. I wish I’d discovered this earlier in life.

The museum will be a magnificent affair. It’s the usual over-pretentious architectural vanity statement with exhibits added as an afterthought by the clients and planners. I’ve seen this so often in my career as a museum scenery designer. Architecture and ducting, bricks and paving, windows and floor coverings can be quantified by number crunching surveyors. Fascinating exhibits rely on creative minds and intellectual concepts. Most clients, especially government or corporate, understand buildings and are keen to make a proud impression by over-designing structures. Yet it’s the content that the visitor will come to see, the majority never noticing the ridiculous feature brickwork and vastly extravagant sloping curved glass window walls. Sometime late in the process the clients usually remember that they must commission the exhibition, at which point poor suckers like me are asked to fit exhibits into totally unsuitable gallery spaces for a minuscule portion of the overall budget. It’s happened on every new museum with which I have been involved – apart, oddly enough, from the last one: the Collings Foundation collection of military vehicles in rural Boston. They very sensibly built a vast dark hangar and allowed us to spend the money on displaying their fine collection. It was an uncommon approach.

This morning we toured the semi-complete museum building, all curved brickwork, glass curtain walls and soaring columns. The team (with just a very few days’ input from me) have done well to plan an engaging exhibition within this pretty unsuitable building, which will be filled with African sunlight that gives so many display headaches. Doubtless the architect will preen about his sloping curtain walls of curved glazing, more suitable for a smart hotel dining room or conference hall… But the public will come to see the dinosaurs. There will be life sized models – formed in reclaimed steel in a very African fashion by a team of Zimbabwean metal sculptors. I encouraged this concept last April and look forward to seeing the work in progress this week back in Durban. There will be replica rock outcrops with dinosaur bones, an infinite storeroom of bones like the stores of Witwatersrand University (an idea I threw up, using a wall of mirrors). There’ll be timelines and artefacts, a replica landscape of 200 million years ago, with dinosaurs, flying pterodactyls and a final exhibit telling the folkloric tales of the local indigenous Basotho people and their myth of a great monster that swallowed villages alive, after which the museum is named – Khudomodomo. This important gallery is being guided by the royal households of the local tribes. We were joined today by a charming, delightful couple, Mpho and Tsolo, wife and husband, members of some part of one of the royal families. Their enthusiasm was infectious, providing us with an enjoyable day, brainstorming, touring local sites, lunching in the smart park hotel and joining us for a presentation by Mike to his clients. The project is well advanced, and the building – as usual in my experience – increasingly behind schedule, almost a year – so far. Also as usual, the deadline for the installation of exhibits doesn’t extend, but squeezes inexorably tighter. I really HAVE seen it all before, having now been involved in some 30 or so major projects of this sort. The exhibit designers always draw the shortest straw and make the most compromises. Ho hum…

Well, as I said, I can wander in and out with no responsibility. I have no fee but receive my ‘payment’ in kind – the chance to visit South Africa as a guest and meet my peers, and enjoy the perks of seeing great places of the world. That suits me as much as being paid a fee!

Golden Gate National Park

Changeable weather rolls about these high places. We’re at 2000 metres. Oddly, I’ve spent most of the past nine weeks or more at that sort of altitude: the Kenyan highlands, around Mount Elgon, Nairobi and Johannesburg and now the Drakensburg. From here I’ll also go up to Lesotho in due course, also at altitude. Tonight there’s heavy rain after a day of scudding clouds, bright sun, sharp breezes, rainbows and chilly winds. It’s a fine landscape. And close by is Lesotho, most magical heart of the globe.

An odd coincidence this morning. In January 2012 I bought a motorbike down here. I found it on the internet and negotiated by email with the seller, a kindly fellow in East London, down the Indian Ocean coast. I flew down and stayed a few days with Garvin and his wife, Mia. Then I rode away. I kept in very sporadic touch, enough that Garvin has my email address. I haven’t heard anything from him for probably four years. This morning I got an email from him, just down the road, in relative terms. He’s Cape Coloured – there are so many racial diversities and hierarchies in South Africa – a biker and a keen rock climber and is about to undertake a fund raising challenge to help purchase equipment for poverty stricken local hospitals where his Belgian wife works as a paediatric trauma surgeon. I was relating the odd fact that he had included me in his email, after several years’ silence, to Kath over coffee this morning. “Oh, I know Garvin! We’ve climbed together. He’s stayed in my house!”

I am in South Africa, maybe 7000 miles from home. I am acquainted with perhaps fifty people in this part of the world. The old cliche is so true, the world IS small, and maybe we ARE all related within seven removes.

Changeable weather – at 2100 metres