TWO WEEKS IN UGANDA, WORKING LIKE A SLAVE. I LEAVE THE GATES OF THE COMPOUND TWICE. I BECOME BUILDER, ELECTRICIAN, PLUMBER, DECORATOR, AND (I hope) WISE OLD TRAVELLER BY THE FIRE PIT AT NIGHT. ELIO, THE FRIENDLIEST COW IN AFRICA DISAPPOINTS US.

Painting the stripes of a zebra’s bum on the walls of the new round house at Rock Gardens, it struck me that I have built the sort of guest house for which I’ve always searched in my travels! Funny, that.

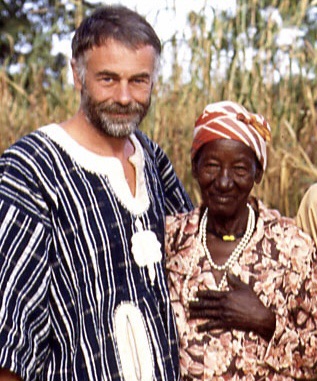

This journey has been different to many others. I’ve concentrated on my African families and travelled independently for only a few days. As the families become an increasing influence in my life, it’s fitting that I spend more time in theirs. And my surrogate grandchildren have become a joy of my journeys here. Funny that in my childless life, I should come to love these two so well in my dotage! Haha. Maybe that’s what happens with age? None of us know, until it begins to hit us, just how to handle old age, that’s a fact of life. We never listen to older people’s experience, always thinking age is something that happens to others. Then up it creeps. Suddenly you realise that the image others have of you, is not at all how you see yourself. I remember my mother telling me she could be shocked to see an old woman reflected in shop windows and it’d bring her up sharp to see what others saw. But did I ever think it’d happen to me? No, of course not. Old age happens to others! But now I am called the ‘mzee’ (old man) and must adapt reluctantly to the fact I am no longer seen as a youth.

Oh well, it’s only vanity. And I can still throw my leg over the (quite high) seat of my blue Mosquito and roar off into the African hills with some aplomb and a good deal of energy. I can still dance about on my footpegs and fling the little bike round the Chinese bends on the mountain roads. I can still be plumber, builder, painter, joiner and instigator of guest houses in rural Uganda! I can paint zebra’s arses on the walls of my grandchildren’s guest house in the hope of making that family independent in the collapsed economy of Uganda.

***

So why am I painting zebra motifs on a Ugandan wall..? I’ve written often of how I met Alex and Precious six or seven years ago, managing a derelict guest house in Sipi, with not much to recommend it but a view across half Uganda. It’s still like that, despite huge investments – in ugly concrete construction by its new owners. It had, apart from the view, one asset: Alex as manager – a fact the current owners didn’t recognise.

Back then, Alex showed me his plot – bare but for a simple earth and stick house he’d built for his small family; just Keilah had been born then. He told me of his plans and ambitions – impossible dreams, more like – to construct his own guest house. With no capital. And I, perhaps foolishly, and certainly innocently, agreed to help – a bit, as I thought. We talked of plans: I told him he should try to attract visitors like me (!): overland travellers and people who wanted an individual ‘traditional’ family stay that they wouldn’t find elsewhere. We came up with the idea of round thatched houses, actually based on a house in which I have loved to stay in Lesotho. I sponsored the first ‘traditional’ house: ‘JB1’.

JB1 led to JB2, a smaller, neat rondavel with a thatched roof of pretty proportions. We had local beds made from tree poles, and I introduced the concept of paints made from local earth mixed with PVA and water. With this, we saved hundreds of my pounds, mining the soil within yards and by chance enhancing the feel of ‘traditional’ decoration, even if I invented it. We eschewed the horrible paint colours so common here, vibrant, unsympathetic hues used by the ubiquitous phone companies. Rock Gardens, named after my Rock Cottage, took on a look and feel of no other guest house in Sipi – itself a stop on the Uganda Tourist Trail, thanks to its tall waterfalls, mountainside situation and verdantly profuse greenery.

But the guests didn’t come… Well, we had a pandemic and the plot is a kilometre from the main road, up rutted and often muddy tracks. We had signposts painted. I made a brochure. Still no travellers found us. Alex remained confident, “Oh, visitors will come. You see!” I began to despair of my – now considerable – investment.

Then some of his colleagues – who now manage his booking system, on commission of course – put Rock Gardens on the unstoppable booking website (soon to extend to the moon, I suspect) that we all know but I can’t write, for fear of inevitable links invading your device as you read. And it went onto Google Maps as well. Suddenly, a bit before Christmas, the visitors started to arrive. This is the new tourism… It’s a concept with which, as I wrote last time, I am out of touch – and propose to remain so. New travellers have phones in hand – as indeed so many used to have their Lonely Planet guides in former days – and move from one place filled with people like themselves to the next. They read reviews and follow an increasingly deeply rutted trail of footprints around the ‘sights’ of foreign countries, leaving so much of what I enjoyed for 50 years – the serendipity of travel – out of their plans and thinking. It ends up, as with the old guide books, with so many staying amongst their compatriots at the expense of finding locals with whom to commune. Now it’s comparisons on phones instead. I, and most older travellers to whom I speak, are happy the world was so much larger and adventurous when we travelled it; brought more sense of achievement to succeed and cope with what chance threw at us.

Still, it’s bringing visitors to Rock Gardens, now the most popular guest house in Sipi, amongst a veritable plethora of competition. Alex and Precious are good at what they do, adding small extras, like greeting new guests with a couple of local bananas or sliced pineapple; bringing them free homemade passion juice and pots of tea as they sit in the gardens with their phones; bringing chairs for chatting guests. “It costs me almost nothing, but people remember…” says Alex wisely.

***

But how do you build and improve a guest house, with many rough edges that the visitors appear to disregard, while it’s full of guests? It’s not easy, I can attest! Much of the past two weeks, we have been firefighting, desperately slapping a coat of paint on bathroom walls even while visitors were approaching from Mbale, down the mountainsides. Uncle Jonathan has been smothered in paint, glue and dirt; becoming plumber, electrician and builder – being better at all than almost all the disinterested workmen in Sipi.

As I painted, I pondered the total lack of motivation and care – the prevalent work ethic in Sipi, probably indicative of most of this failing country. The workmen available, self-styled at their trades, come only to do the minimum and get a pathetic pay packet at the end of the day. They care not a jot for the quality of their work; they use copious amounts of materials without any economy; they create a godawful mess; do third rate – at best – work; fail to clean up before leaving – and then steal any tools they can lay their hands on. It’s depressing and disillusioning, and infinitely frustrating. I make a fuss: insist on cleaning the site, rail about low quality work, sack the ‘electrician’ who has no more than insulating tape for 240 volt connections and leaves two bare three inch copper strands hanging at child height without any protection – and leaves the site for the day. “Oh, take care, those wires are with electricity!” another worker tells me next morning, before I hit the roof, as Keilah and Jonathan almost electrocute themselves. “And don’t come back!” I yell at the irresponsible ‘electrician’, and proceed to turn off the power and fix the plug socket – to which the ‘electrician’ has lost the box screws, so I must tape it together… Later that day, the ‘electrician’ phones Alex pleading for more work. “Talk to the mzungu!” he replies with a private smile. Most workers don’t come for a second day when I am directing work!

So, I’m wondering, as I slap brown earth paint on the walls of JB3, just why there’s this total lack of responsibility and commitment? Why the poor morality, the jealousy, the cheating and petty thievery, and the mild aggression, corruption and greed of this country, otherwise so friendly when commerce isn’t involved?

I decide it’s the inevitable result of lack of moral leadership. When you look up at your leaders and see cheating, lack of concern, arrogance, vanity, robbery (why call it corruption?) and nepotism, why would you think integrity, honesty and compassion pay off? The message and lesson is that only cheating your fellow moves you forward. Thus greed and jealousy, graft and petty crime appear excused and become accepted behaviour, such that honesty and compassion for others become weaknesses. And it’s no longer an African problem…

Look at other leaders: the Trumps, Johnsons, Goves, Camerons, Lord Snootys, Putins, Melonis, (insert names yourself) of the world and understand why 2024 is so socially unpleasant and alarming. Totally uncaring people. What examples of moral leadership are they? Thatcherite greed is the way you get up in the world. Look after Number One. I’m alright Jack… I think it was Denis Healey who so succinctly summed up the morality of the day: “Margaret Thatcher turned compassion into a weakness.”

The recipe for modern times…

***

I’m so proud to watch Alex and Precious buck the trend, gain respect from their visitors and become exposed to so many influences. There’s no doubt Rock Gardens is a roaring success and the most popular of the plethora of guest houses in this greedy, commercially aggressive tourist town. I’m delighted that my instincts were spot on seven years ago.

Some charming visitors are now enjoying Rock Gardens. Sandra and Fiona, from Germany and Leicester, turned up on a VAST, heavily loaded Triumph 900cc motorbike. They even carried camping chairs. Both slight, Sandra is pernickety and likes things done sensibly and with logic, the German way. Fiona is more easy-going and adaptable. “I think it’s a woman!” whispers Precious in amazement as the two helmeted figures ride through the gate. They take the only room left, JB5, a room with no bathroom. I reckon Sandra will only stop the night; the latrines are basic, to say the least (lots of work required yet) and at the bottom of the plot. But they enjoy the atmosphere so well that they stay three nights and we all bond. They might even visit me in Harberton in April!

Haruto from Japan, is a youthful charmer. Slow to join in, by his second day, he’s bonded with Precious and is sitting on a low stool in the kitchen watching her cook and helping her with the endless hand washes caused by so many guests. The garden is festooned with bed sheets.

Anja and Peter are from Denmark, Anja of Greenland parentage. We have fascinating conversations by the fire pit, about the competition of USA, Russia and China over the vast wealth of unknown resources that will be exposed by the melting glaciers, riches unseen for ten million years. And the ocean passages that are opening across the polar region. They come for a couple of nights, stay three, go away for one – and come back for a fourth night, they are so relaxed at Rock Gardens. Anja brings sparklers for Keilah and Jonathan.

Helmut, a 70 year old biker from Germany rides in, also on a huge machine. He’s come from Namibia and hopes to ride back up the west coastal route. He’s frightened by an attack of vertigo. Head spinning and unbalanced. I’ve had it a few times and can comfort him that he’s not having a stroke on his African safari. “Sorry, chum,” I say, “it’s age-related!”

***

Guests come and guests go. All are charming, cooperative and relaxed about the building works and compromises they must make to live in our rough-edged place. Alex has to juggle rooms constantly and I must rush in, wet paintbrush in hand whenever I get opportunity. The rugged kitchen, made of wood and cement last year, when I decreed, “You can’t cook for mzungu guests on the floor…” is constantly in operation. Alex is rushing from buying building materials, matoke, ‘Irish’ and chickens to preparing meals and advising his guests. He falls asleep across plastic Chinese chairs by the fire. I don’t get to leave the compound for eight days, except for a quick run to the bank in Kapchorwa, 17 kilometres away, for more money. I wear the same socks, tee shirt and grubby shorts every day. I travel light and can’t afford more clothes spattered with mud and homemade paint.

***

But my greatest relief is in Joshua. Joshua is a young Sipi worker, usually words that fill me with gloom. But Joshua is great! A quiet, charming young man, he is self motivated, thoughtful, economic, cares about his work, and gets calmly on – doing excellent work. It’s a first for Sipi. He’s first to arrive, last to leave – and even cleans his tools at the end of the day! Here in Sipi, he expects to be paid a mere 20,000 Uganda Shillings for a day’s work. That’s a little over £4! It’s obscene to think what I get paid for a day’s work in America by comparison… But it’s more than most are worth. The first few days, I tip him an extra 3,000, and he’s quietly delighted. By day four, I up his pay to 30,000 and compliment him every time I pass. He’s restoring my confidence. We work together happily. “We have to keep Joshua as our builder!” I instruct Alex.

Joshua tells me he has two children, a girl and a boy, and that that is enough: wise thinking in this crumbling country where education is so poor and families of such numerous proportions. As I write, back in Kitale for two days (to do shopping for materials just impossible to source in Uganda), he’s making stepping stones in moulds we’ve invented from plastic paint containers and carrying out various works to upgrade the latrine. He has weeks of work. I trust him.

***

One day only, Alex and I get out for a walk. We both need wider views and to forget the work for a day. We drop down onto the edges of the great plains below Sipi’s escarpment and wander in green matoke and coffee for a few hours, before the inevitable puffing clamber up the cliffs again. But we approach too close to one of the waterfalls for my pleasure. Whenever we get close to the attractions of Sipi, there’s jealousy and commercial tension that Alex is ‘guiding’ me for free – my son-like companion. So-called guides compete for business here and insult him and argue over the pennies they lose by me not being a customer – a wallet on legs. A mzungu. We are seen as no more than cash machines. I prefer that we walk away from the town into rural areas, where I am an excitement for children at a crude mud primary school who break into a welcome song for the visiting mzungu. This is why I travel; not to watch water falling over a cliff – something I can admire as I ride past on the road on my piki-piki.

***

One Rock Garden’s afternoon, we suffer a thunderstorm and cloudburst of biblical proportions! Rain dislodges fir cones like bombs from the high pine tree in the middle of the garden.

In minutes, we are all stuck in the kitchen, unable to talk over the machine-gunning on the tin roof. The garden becomes a roaring river; the lawn becomes a lake. This should be the dry season, but this is Climate Change at its most extreme. Almost every day we have showers. In the ‘dry’ season… It’s vibrantly green everywhere, but no one knows if they should plant early or wait out the vagaries of the weather and risk failure of crops. What to do? This is the reality of Global Warming, as suffered by those who create the least pollution, but rely most closely on the dependability of regular seasons.

Another consequence for ‘The Money’ of Rock Gardens is that I have to take off the thatched roof of JB2 round house and replace it with corrugated metal, with straw on top. An expense we could have done without. But having dried ALL my clothing and possessions after the storm – fortunately it was me sleeping there that day – it’s an inevitable choice. We have to take the room off the booking system for five days or so; I move into the unfinished, rather damp, new round house, bucket-wash in a corner of the garden, pee in a bucket at night – and workers make the new roof. Then we have to completely renovate the house.

One day, Mark the barman comes to me and says, “Uncle Jonathan, I need 50,000 for a crate of beer…” I’m tired and I flip: “Why don’t I pay for the bloody visitors’ holidays?” Then Alex comes for money to buy goat-meat for their supper… So, Alex and I have an important conversation. “Separate Operations from Building. I pay for construction, you take operational funds from income. I’ll invest more money to get the place up to scratch for all the new guests, but YOU pay the bills.” Trouble is, he’s embarrassed to request funds, coming to me endlessly for small sums, when his pocket is empty.

With all the zeros in Ugandan currency, it all appears SO expensive! So, I transfer money to him and he pays the bills. It seems less that way, even though it counts in hundreds of pounds, not millions of an almost useless currency! Odd thing, perception…

Oh well, it’s a good way to spend my pension..!! Haha.

***

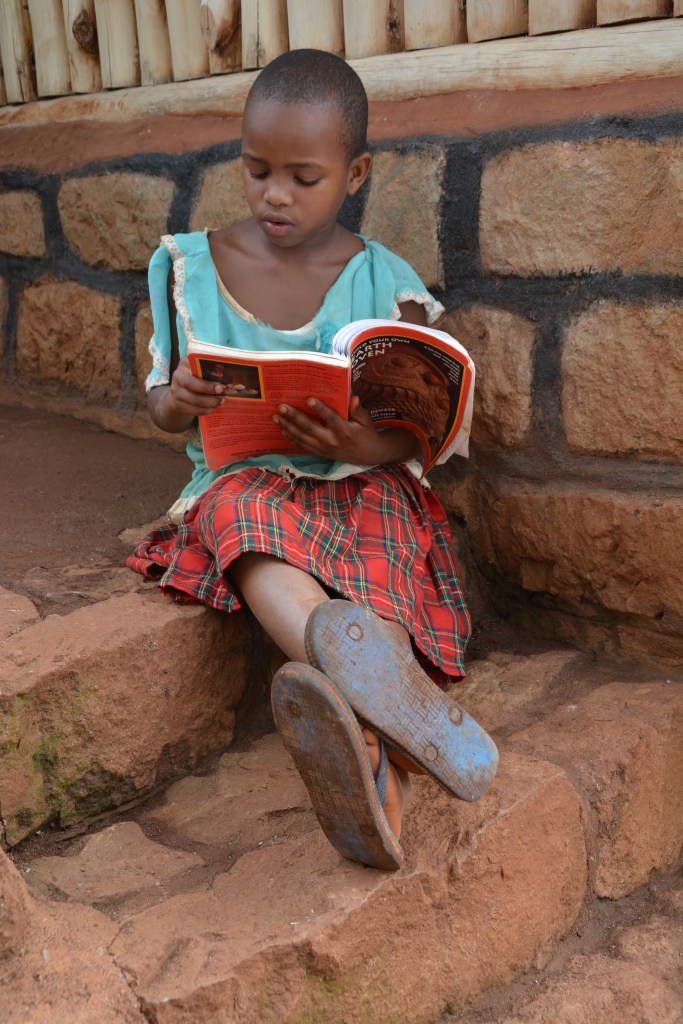

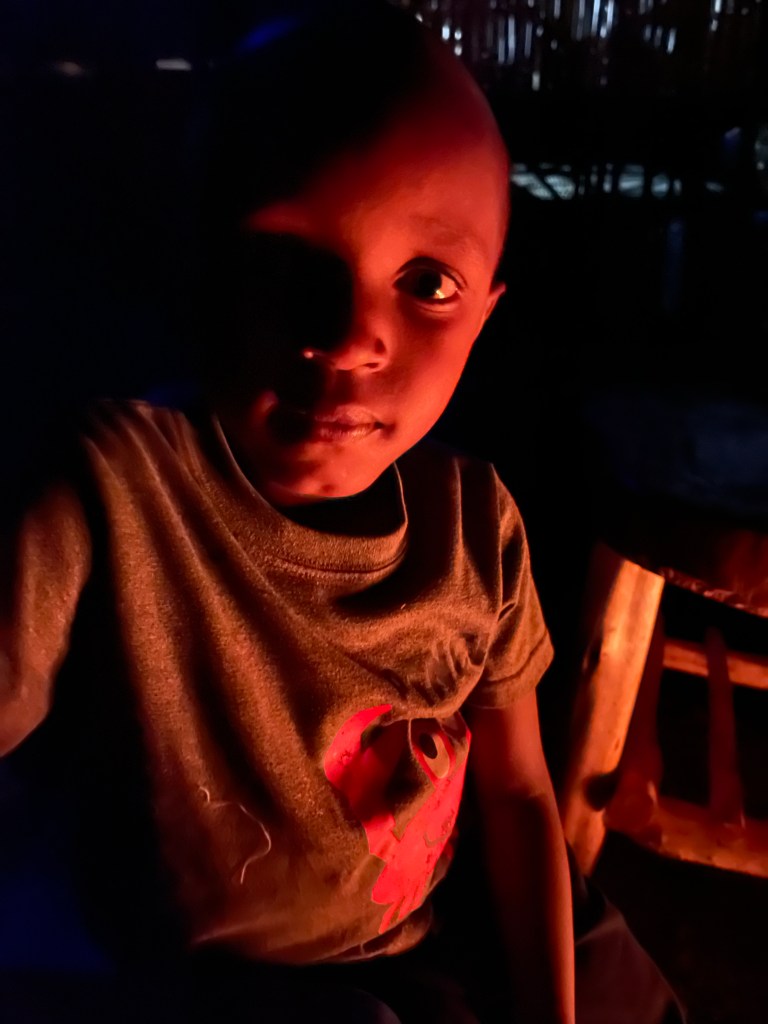

But with all my work – and the idea of lying on a beach reading a book is anathema to me as a holiday – I need activity, and this building work suits me just fine – with all that, it’s the children who make my stay so wonderful. I’ve come to love these two so much.

However, they now board at school. It’s odd how much I miss them during the week. It may seem callous to send a five year old and seven year old to boarding school. It’s just another reality and practicality here. The government schools locally available are worthless, so Keilah and Jonathan go to private primary school in Kapchorwa, ten miles up the road. For their first years, they were picked up in a school van at 5.30 and returned at 6.45 in the evening (Jonathan was three when that regime started). The van can’t get to Rock Gardens, on its filthy mud track, in the rainy season, so Alex must walk them a kilometre to the road. “Huh, it was costing me in shoes for Jonathan!” and the school van, often out of service (maintenance only when school fees are in, so usually not running for the first days of term…) carries about 50 children. The road to town is extremely dangerous and the drivers tired. So Alex made the decision to board the children from Monday to Friday. The cost is a bit balanced by not paying for transport, and the children get basic food and accommodation in rough dormitories. And accept it with pleasure! Both love school and are bright, intelligent small people. It’s only we who miss their cheerful company and Jonathan’s endless chatter. “Uncle Jonathaaaan…” His school clothes are embroidered across the bottom: ‘Cheptai Bean J’.

So I make sure I am there for two weekends, and have now returned to Kitale midweek, to ride back tomorrow, Thursday, laden with floor paint, zebra fabric, shower curtains and tile cutter, to work again for a few days. My time is running down now, just 18 days to go before I am back to the rain and gloom of Devon. At least after rain here, the sun shines again! It’s been a different visit: Family, not Adventure. But for an obsessively independent old bloke, maybe family IS an adventure! Here in Kitale, I am welcomed like a brother and uncle; in Sipi a father figure and grandfather. Not a bad development in life! Not bad at all.

***

But I still haven’t told you why I was painting a zebra’s bum on a wall in Uganda!

I’d painted zebra stripes in JB3, in panels on the wall. I brought some prints taken from the internet as inspiration, and developed a blister on my finger freehand painting with a small brush, nasty black oil paint on vinyl silk from Kapchorwa. I needed to ‘round off’ my design into the bathroom area. “Has anyone got a connection to get me a Google Image of a zebra’s backside?” I asked at the fire pit. Fiona went one better. “Here, it’s pictures we took in one of the parks!” Close ups of those bizarrely beautiful animals. And their backsides.

So, round the corner of the bathroom entrance, I extended the zebra panel into a flapping tail. A visual joke we all enjoyed.

***

In another room, I painted an illustration (in brown earth paint) of the round houses and the tall pine trees. In front, I drew Elio, the cow, the friendliest cow in Africa, who actively seeks human company. One night, by the fire pit, she puffs heavily beside us. She’s pregnant and Mark, the barman, has worked with cows. Everyone lifts her tail and views her backside. Silly animal, she loves the attention. Mark declares that he thinks she’ll soon give birth, maybe next day. How exciting, Alex and I think, as Precious rubs Elio’s neck in sympathy. Amusing animal, she loves it.

How disappointed we were, not to wake to a new Rock Gardens member, but a big fat cow that had had indigestion..!