AFRICAN FAMILIES

23 JANUARY 2025

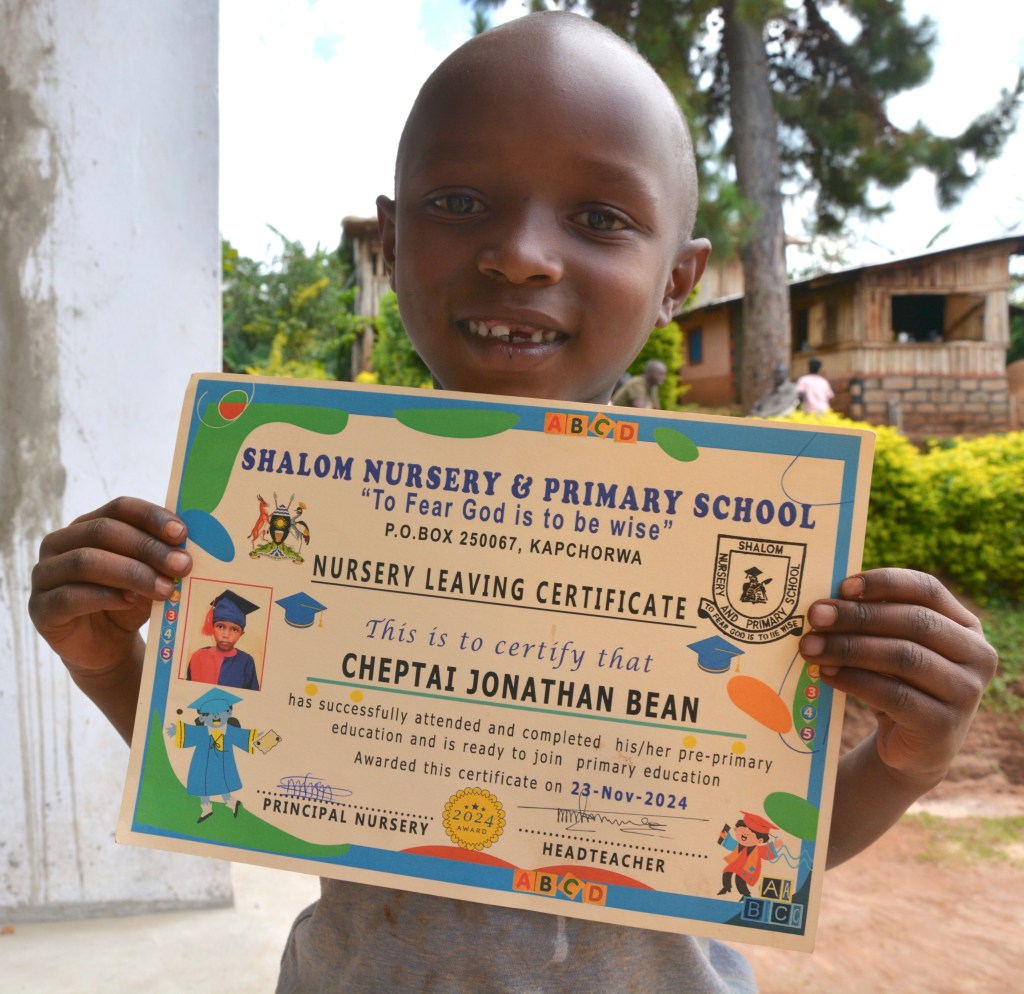

On December 28th, I arrived in Sipi, Uganda, home of my ‘Ugandan Family’, Alex, Precious and the two lovely children – my surrogate grandchildren – Keilah, eight and Jonathan Bean, six. I so much enjoyed the children’s company that I stayed over three weeks. And in answer to the common question I am asked at home, “What do you DO in Africa?” I can only respond, pretty much what I do at home: work rather hard and expend a lot of energy on practical projects. My ‘rest days’ involve long hikes up and down very high mountainsides… It’s a perfect ‘holiday’ for me: plenty to do physically, sunshine to do it in, and well fed and sufficiently beered by my hosts. Warm beer, of course…

My practical role is to provide design advice, paint and decorate the houses and redo most of the work done by inept Sipi workmen. Two of the new rooms had water drains connected directly to the soil pipe, without U bends, resulting in foul gases pervading the rooms. This, by an arrogant ‘plumber’ I dislike, who exploits Alex’s total impracticality. I’ve had to replumb most of his work. Twice, I lost my temper big time, berating ‘workers’ who refuse to invest in tools and rely on the bent hammer, a machete and hoe to do carpentry, make furniture and fittings. Tom, the wood butcher, won’t now come to Rock Gardens if I am there!

Our quirky guest house, named after Rock Cottage in Harberton, comes along apace, with its six detached round houses. Actually, one’s rectangular: the Kampala Bungalow, as I rudely call it: Ugandan guests don’t want to stay in the ‘old fashioned’ thatched houses so popular with mzungu guests! The place is unique, with its quaint wooden restaurant up on stilts, its excellent food and its welcoming atmosphere that feels very ‘African’ by design. We are attracting many customers; some days, it’s booked to capacity. Just a day or two ago, we hit a record of 15 guests, having expected a quiet day with just two and me. That night, we had two young Israelis sleeping in a tent, one under the stars and all rooms occupied, even the ‘emergency’ rooms – the rather basic ones in the original family block. It begins to make some money for Alex at last; it must do, because the demands on my wallet have reduced. I still pay much of the capital cost, but running costs and maintenance seem to have devolved onto the Rock Gardens cash box, such as it is in a hand to mouth economy. It’s still the biggest expenditure of my life, with all my pension coming here, and a good deal more to the other African families, but I am financially secure now – something I never planned nor expected, but a benefit of being of the Baby Boomer generation, perhaps the most fortunate in history.

All this gives me the opportunities to indulge my passion of travel. For decades it wasn’t this easy; I had to make choices – sometimes difficult ones. I remained freelance and childless, I sometimes had periods of relative poverty while I had no income, and I always scrimped and saved for my journeys. Obsessively, some would accuse! But in the end, it’s all worked well, and I now have chosen families in several countries and can share some of my privileges. I can also travel pretty much at will, despite the economic turmoil of the world.

****

It’s been great to be in rural Africa, totally avoiding all recent ‘news’. I’m told that the ignorant reality TV failure, now ‘leader of the free world’ (derisory laughter) who called all Africa ‘shithole countries’ did not invite a single African leader to his recent inauguration. Having studiously avoided even opening my Guardian subscription for over a month, I’ve been able to avoid witnessing the degradation and shame now being visited on the people of USA. Poor USA is now the shithole country. How angered he’d be to know how Africans laugh at him with such derision!

****

We hardly ever meet Americans travelling in Africa (except for hunting and expensive safaris: very few backpackers), but if more Westerners travelled in Africa (and thank god they don’t!), there would be a lot more understanding of the modern problem of immigration, and the reason that so many are willing to risk everything, even their lives, to achieve the vain dream that so many Africans (and Latin Americans) harbour: that riches and ease of life await them in the rich countries of the North.

At least every day, I converse on the futility of the African Dream. The Dream is that by getting somehow to Europe, Australia, Canada, USA, all problems will disappear and wealth will flow without limit. To understand it all, just look at what Africans see of life in our countries: not poverty, homelessness, white beggars, unemployment, racial prejudice, meagre living conditions, bad health, child poverty, unfair opportunities, divisive education – well, I could go on. What they DO see, on TV and media, and now overwhelmingly in the exploitative videos they watch endlessly on their phones, is glamour, rampant consumerism, commercial exploitation, wealth, fast cars, palatial houses, fashion, possessions, triviality and untruth: the myth that you are what you own. It is unfiltered, made to exploit, made to create customers. This great lie is taken as truth. It’s on TV. It’s on YouTube. We all live like this in our rich countries.

And of course, the only mzungus they see are tourists. I explain that we tourists are APPARENTLY wealthy when we come here because of the relative value of our money. But how do I make people BELIEVE me? I tell them that my 20 bob cup of tea in Kenya (12p) will cost them the best part of 500 bob in England. That a cheap room to rent in London will cost them at least 130,000 Kenyan shillings (say £800), and that if they are fortunate enough to even GET a job legally, they are likely to be on minimum wage (£10.90 I think). A meal will cost them that much, a bus fare to work a minimum £3. I tot up my monthly electricity bill in Ugandan and Kenya Shillings. They gasp. It’s more than most earn here in a month…

But The Dream lives on. Not a day goes by without someone asking me for help to reach Europe. Marion, a smart, clever young woman working at the Kessup guest house, passed out of school with the highest marks: university place almost guaranteed despite, William informs me, coming from a very humble family. But she’s fixated on The Dream, which will solve all her problems and make her rich. I point out that if she has any hope of raising the airfare, visa costs and the probably exploitative fees for some unknown university in UK, that is most likely nothing more than a sham business, then she has every chance of raising the deposit she needs to secure a government loan in Kenya to study at university, without wasting her resources on the chimera of The Dream, and suffering the prejudice, climate, restrictions and dislocation of family and culture. Stay here and do good things, where you have friends and family and are culturally secure, I tell her. She appears to take it in, but the lure of The Dream and all its glitz and glamour is very persuasive. Life to most young East Africans is on their phone screens now, and all they show is the consumerism and superficial wealth of our countries. All fake. All exploitation.

I’ve seen the other end of The Dream: Africans living in austere conditions in illegally sub-let council flats in London; a trained doctor selling train tickets for British Rail; a smart Ghanaian woman married to an elderly British manual labourer of very little education, living in a dowdy mobile home in dismal Lancashire; the prejudices flamed by the rightwing hate-speech of the Reform Party and their ilk; the inflammatory language of the Daily Mail and rightwing TV; violence of the ignorant; selfishness and mean-spiritedness of so many ‘superior’ white people. For god’s sake, I was just in Texas for the Trump election, so I’ve stared into the depths of the abyss! I’ve seen how mean and selfish man can become, when his own livelihood is threatened. That’s why Trump succeeds in his vicious, lying poison.

But this is the reality behind the desire to get to Britain, despite the appalling risks. Britain raped and pillaged for 150 years, and through some ancient propaganda, many still see those times as secure and stable. “You were our masters,” they say, with a misplaced nostalgic respect for a time when politics were stable – because dissent wasn’t allowed.

This is why so many risk all, even their lives, to reach The Dream… It is impossibly sad. I’m ashamed to be upheld as an example of living The Dream. I know the reality is SO devastatingly different… Poor exploited Africa.

****

Last weekend, Alex and I rode to a HUGE, extravagant wedding in Lira, in the middle of northern Uganda, 170 miles away and a couple of thousand feet below Sipi’s mountain shoulder elevation. On the first night, we stayed in Dokolo, in a calm, cheap £5 hotel of round thatched houses, setting off early next day to catch up with the Kapchorwa clan in Lira.

Thank goodness we decided to ride there. The local clan, from Sipi and Kapchorwa, travelled by a school bus, driving half through two nights, while we enjoyed a couple of nights away from home. The clan members are expected to attend, but it appears that the bride and groom, a mature couple with three teenage children, paid for everything. Alex guesstimated that the whole event may have cost at least £6000 or £7000, a massive sum in Uganda. It was a fine example of high African bling, and an occasion to dress up: women wearing all manner of African fashion, from traditional swathed African print dresses to clingfilm-tight fabrics that left little to imagination. The men, as usual, wore ridiculous, impractical, ill-fitting western suits (not me, of course, for I have only a pair of slightly grubby zip-offs and a relatively clean, crumpled long sleeved shirt!)

The ceremony began in a big born-again church on the edge of sprawling Lira, an unattractive, surprisingly large town on the hot, swampy plains of central Uganda. 500 people packed into the tin-roofed church, including one very conspicuous mzungu, making it impossible for me to get out my phone and read a book during the extended shouty sermons and formalities by half-crazed business pastors. I could understand nothing, with the amplification of chest mikes, and exaggerated accents. I sat – as I have become accustomed in so many African events – with a smile and look of apparent interest fixed on my face, the sinecure of a thousand eyes. I’ve no doubt that the bride and groom, when they sit to watch the HOURS of video, will wonder who the hell the freeloading mzungu was! If they were listening attentively, they’d’ve heard me introduce myself on the microphone, as requested by a ranting pastor, to the entire throng. My years as a mzungu in Africa have accustomed me to such spotlit moments.

The ceremony over, we repaired to the Lira Hotel for a splendid glittering wedding feast, with gazebos decorated in orange and white furbelows, gold-encased Chinese plastic chairs and a white and orange arched bridal walkway to the high table with its acres of fake florality, golden chairs and backdrop of autumnal Canadian woodland. By some odd chance, Alex and I were not directed to the Kapchorwa clan tent, but to the ‘Church’ tent, a source of much private hilarity for a couple of avowed atheists. One of the pleasures of the serendipity of travelling is the play acting often required. And as members of the ‘Church’ contingent, we were then ushered to the front of the pressing line of hundreds of jostling diners, anticpating a free meal. A good meal it was too, cooked by outside caterers and served with aplomb by the hotel staff.

Speeches were long and very tedious. Give an African a microphone and they seldom know when to stop. Everyone must be introduced and their status paraded at length, all pride and name-dropping. The MC decreed two minutes per speaker. Some chance. He gained a round of amused ironic laughter when he wrested the microphone from the bride’s sister after 25 minutes of tedious introductions, suggesting that we had already met every one of her aunts, uncles, sisters, nephews and nieces, and her children could just wave from the crowd to satisfy the final introduction he was allowing her. We all applauded the MC.

We were entertained by a small troupe of male dancers from the northern Karamajong region of Uganda; energetic and lithe, they danced frenetically and often with humour. One supple young fellow was particularly humorous, dancing provocatively feminine roles to great effect with shaking bum tassels. They leaped in fast acrobatics, formed human towers, somersaulted through hoops and breathed fire. It really did seem that no expense was spared by the bride and groom – a professor at one of the universities. But quite what they thought of the unknown mzungu, now an honorary part of the Kapchorwa clan, I do wonder.

Alex and I stayed the night in Lira and rode the 170 miles home on quiet Sunday roads across the flat interior of Uganda, where swamps and sinuous lakes make up some of the landscape. It was my third ride through the area, but Alex’s first, an experience – and well earned rest we both relished.

****

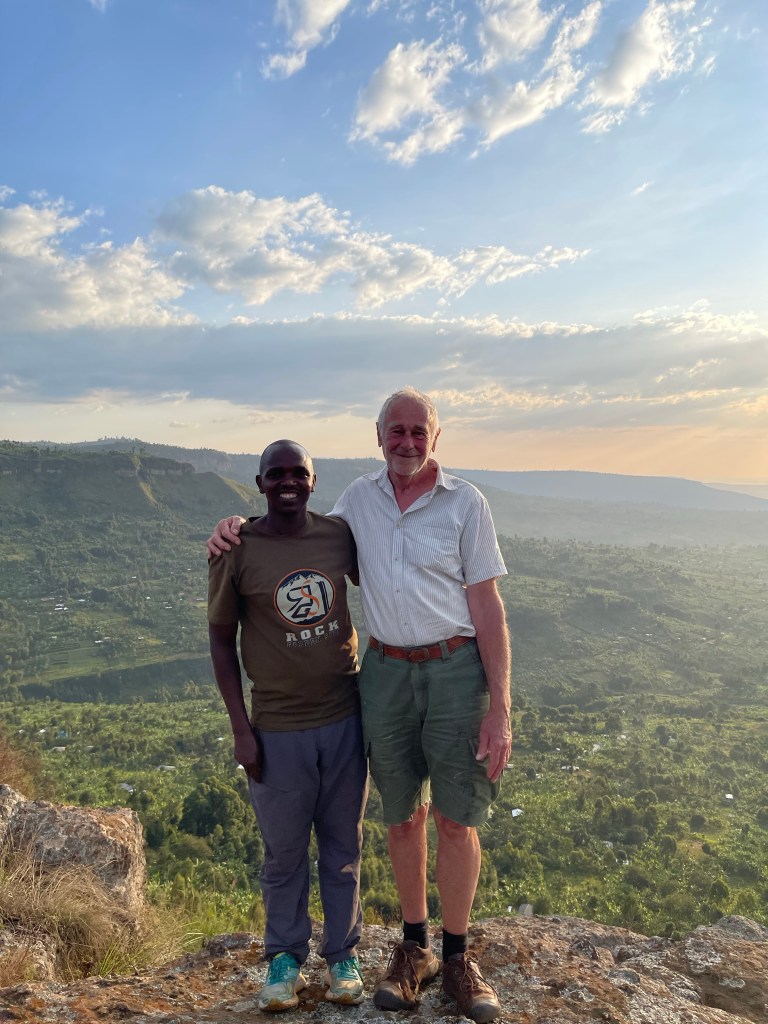

In Alex, I see a lot of myself… It must have been this early instinct that formed the bond, that first evening, seven years ago. Funny how instinct is often the surest guide.

In him, I see shades of my own somewhat obsessive, sometimes compulsive nature, my restless need for activity and order, my extreme sense of justice, impatience with meanness of spirit and my irritating ‘White Anglo Saxon Protestant’ work ethic, to say nothing of my obstinacy! Half my age, he never stops, is upset by injustice, has a great sense of integrity and thinks and plans ahead, vanishingly unknown qualities in so much of Africa. He’s become a steadfast companion, it’s easy to travel together, especially away from the stresses of Sipi. We both like people.

****

A day’s hiking in the rural beauties away from the tourism of Sipi, is Alex’s and my idea of relaxing, despite the energetic nature of walking in this steep country, with its dramatic cliffs and red mountain tracks. It’s hard countryside to tame, prone to many serious landslides and with tiny terraces of fields battled from the steep slopes over many generations. We seldom pass beyond populated places, every inch used for subsistence crops. But we DO get quickly into areas where a white visitor is rare, and I am feted all day by countless excited children (in this country where half the population is younger than 14 years) and shake their grubby hands hundreds of times. It’s fun progressing through in this celebrity manner. Alex and I chuckle at the antics of distant, often invisible children yelling, “Mzungu! Mzungu!” and calling their friends to look.

One day, we clamber down the ladder on the cliff near to Rock Gardens and drop to the slopes below, following a sinuous red dirt road through lovely scenery and many hamlets. At every house, crowds of children gather to stare and call. We stop in a scruffy village on the steep slopes for tea and chapatis. The people tell us that their community is due for resettlement to the hot dry plains far below, after the giant landslide that buried 12 hamlets and about 200 people last rainy season. Climate change is making many disasters in Africa, the continent that causes least pollution and is least prepared to deal with its consequences.

We’ve spotted a track winding up the steep slopes. It rises from this decrepit hamlet. It’s a huge staircase of rock-built steps, rising over 650 feet! It’s a rarity here, where the paths are always informal, made by a million plastic flip-flops and Chinese sandals over many years. It’s amazing! A giant stairway to heaven, built in 2024 at the behest of a rare generous politician, the local MP, to get his constituents up this precipitous mountainside.

The steps end at a metal staircase, the last 100 feet up the cliffside at the top. Unfortunately, a rock slide has already carried away the top 30 feet or so and it’s been replaced by the usual rickety stick ladder above a dangerously slippery rock face. Some acrobatics are required above the cliff face to transfer from formal steel to the crazy sticks.

At last we are on top. We’ve climbed over 1300 feet since we spotted the path, straight up the side of the mountain, and now stand well over 6500 feet high. The air is thin, it’s good training. The views are magnificent from up here, but I know that our hike home will be relentlessly up and down, and still three hours or more. It’s great to be here. Great to be in rural Africa, with a smiling companion who treats me with fatherly respect and fondness.

****

It’s now January 23rd. A couple of days ago, I rode back round Mount Elgon to Kitale. What used to be a derelict goat track that took all day to ride, and made me arrive beaten, battered, smothered in dust (and highly exhilarated), is now a smooth road belonging to the Chinese government. “Cheap loans from China are VERY expensive!” I say to the staff at Suam border post.

The journey takes a record short time, door to door in two and three quarter hours, including half an hour of bureaucracy crossing from Uganda back to Kenya.

We are expecting Wanda and Jörg to visit today. I met them on my travels about four years ago and we became instant friends: an older couple from Köln, with an old camping car that they keep in Tanzania and use, like me, to escape from winters in Europe. They made friends with Adelight and Rico and now stop by most years on their wanderings.

As at the remote international border post, where I’m known by my first name, I’m recognised all over town in Kitale; even the street traders welcome me back, the shopkeepers, supermarket staff, all give me warm welcomes. What is there to be afraid of in Africa, the commonest question I am asked at home? Implied, of course, is a immense misapprehension of Africa, encouraged through 150 years of English culture, as we colonised and controlled ‘the natives’. Buried in the question is a huge sense of cultural superiority. It’s all so far from the actuality of what’s around me; of what brings me back year after year; of what’s caused me to form families across this misunderstood continent – where I am greeted hundreds of times a day, made welcome, respected and befriended.

****

Next week, I’ll ride back to Sipi. We have to find a better school for the two children. The quality of education in Uganda is abysmal, and they have not been doing well, despite their intelligence, at the best school available, 10 miles away in Kapchorwa, where they had to board thanks to the dangerous driving of the school minibus, packed with small children on the dangerous road. It’s likely that they may have to travel to Mbale, 30 miles down the mountain, to find a better education. Life is tough in Africa. Whatever age you are.

This year’s journey is remarkable for my delight in the small people around me. Perhaps they – and I – am at an age to appreciate this. Keilah is the eldest at eight, followed by Maria in Kitale at seven, Jonathan in Uganda at six, Wesley in Kitale at five and his brother, the wonderful Wayne, whom I could pick up and bring home, at eighteen months, a serious little boy with the biggest eyes and a habit of attracting attention by tapping you, rather than speaking.

I’ve come to adore them all! A fine gift for the mzee mzungu – the old white man! They are making this safari a delight. Who’d’ve thought it?

****