APRIL 2nd. THE END OF ANOTHER SAFARI

When you travel in these parts, the Equator becomes something of a feature. On some roads, I ride across it several times in just a few miles. Hiking at noon on the 22nd of March, 43 miles north of the equator, just 55 hours after the equinox, I asked William to take a picture. I really DO walk on my own shadow. Here’s proof:

****

A week later, as I bus through the highlands, it amuses me to watch one of the free apps on my phone, the compass that reads my altitude and location. We approach the Equator, tantalisingly slowly on the winding road, counting down the degrees, minutes and seconds of latitude and longitude, and the altitude.

Conveniently, latitude and longitude were invented in the old imperial days, and a degree of latitude is 60 miles so every minute is a mile (which, inconveniently, makes a second a 60th of a mile, 29.3333333 yards – revealing the clunkiness of the old imperial measurements).

Up here, we are very high. The bus grinds along in a line of labouring articulated trucks, matatus and the slowest of lorries. This narrow, winding main highway carries all the petrol and commercial traffic to Uganda and the interior of Africa from the coastal ports of the Indian Ocean still 400 miles away. The numbers count down slowly. The views are big, superb up here: forested slopes, dark conifers and flowering deciduous trees, high altitude meadows, giant vistas down to the south, red earth, and over it all, the cloud-dotted blue African sky. Women sit behind pyramids of delicately balanced red potatoes and cabbages like green footballs at the roadside. Most wear old mtumba anoraks and bobble hats, despite the extreme sun. To them, it’s cold! Could be down as low as 23/24°!

We make a sharp right curve and head south for five miles or so, through the straggly village of Timboroa. From here, the degrees count down at the speed of the bus: we are driving due south to the Equator. My phone tells me we are now at 2740 metres, 2750, 2760… At one and a half miles, 2790. One point two miles, 2820; one mile 2830; nought point six miles, 2840 (9318 feet). Then just 800 yards north of the Equator there’s a disappointing downwards tilt from this highest point on the road to Nairobi.

We cross the Equator at 2800 metres (still 9187 feet). The numbers, for just a moment, read 0°0’0”. We are 35°32’8” round the globe from the other invisible line through Greenwich. A tenth of the way round our planet. Amazingly, there are railway tracks up here. Those colonial Victorians certainly had ambitious confidence. The line’s being restored by the Chinese now: the next imperialists for poor beleaguered Africa. I saw a ten-car goods train lumbering towards Kitale the other day. With luck, it might get some petrol tankers off the high altitude road one day.

Then we are in the southern hemisphere. We roll past the village of Equator. Home, my phone tells me, is 4175 miles away. It feels every inch of it!

I wonder how many points on the Equator are this high? Was I up here in the metaphorical clouds that first time I bussed over the intangible line in Ecuador, fifty one years ago? I wonder how high I was on the Pan-American Highway on my way to Quito, itself about where we are now, 9350 feet?

Fifty one years… Ouch. Brian Tammen – a long haired, blond young American. We travelled together for a few days. We shook hands with portentous gravity as the concrete globe on a cement pedestal whipped past the third class bus window. I wonder where HE is now..?

Fifty one years. When you’re young, you never imagine being old…

****

Let me go back. A few hours after the equinox on the 20th, found me hiking into the Kerio Valley, down again to the burning equatorial depths, home of the world’s best mangoes and one of my favourite bits of East Africa.

There’d been rain in the night, quite heavy, machine-gunning on the tin roof of my room on the lip of the great valley. Clouds hung like fog above and below the Kessup plateau, which William calls the ’hanging valley’, a thousand feet down the wall of the Great Rift. It made for cooler walking.

William and I could march along, using the putative road to the valley, which somehow ran out when the contractors hit 850 vertical feet of friable escarpment wall. William says cynically, “Huh, some officials made a LOT of money from this road!” The ‘road’ doesn’t actually exist, running out eventually and we must take to a steep slippery footpath and stumble down to where it starts again. The project is perhaps six or seven years old and already turning back into a goat track.

****

We stay down on the Rift Valley floor, 2700 feet below Kessup. At least the heat of our last stay at Kipkoiywo Guest House has dissipated a bit. It’s just HOT now, not burning hot. But the start of the rains has brought out multitudes of flying ants and other insects. There are vast numbers of beetles on the ground, long black ones copulating furiously, small fluffy scarlet ones bustling busily, and many more. And this evening in the hotel yard, attracted by the light, I am plagued by flying insects by the hundred.

Beside my bed in the extremely basic guest house (and remember, I’m a connoisseur!) I find a crumpled leaflet.

‘Kipkoiywo Guest House is the combination of innovative design and crafted luxury and set apart by an unprecedented level of personalised hospitality… We combine comfort, personalised service and bespoke journeys… Exceptional values… Full time water availability… This is a place that is fun and filled with the unexpected…. And mindful that less is so often so much more.’

Actually, of course, less is often so much less. It’s a block-built hovel like all others, where the surprise is that there’s hardly any food available, no drinks; the rooms are completely basic: a bed, plastic basin and a pillow made from old foam rubber blocks. There’s no water except a battered jerrycan. The bathroom is an unpleasantly grubby unwashed latrine; the place is bonfire hot and bakes beneath tin roofs. For breakfast, if you’re lucky, you might get a couple of dry chapatis and black tea. Crafted luxury! ‘Your dream holiday destination’. Indeed… Another broken African dream; big plans, no reality.

****

There’s not much to stay down here for, except the luscious mangoes. We’re really here to climb out again. Odd behaviour, unless you are addicted to hard hiking and have experienced that view of the huge valley expanding below as you clamber up its side. The routes up are impressive, but perhaps the Kabulwo track is the best way back up that we’ve discovered so far. We did this extreme climb two years ago. It was even hotter then. It’s terrific to see the snaking track zigzagging across the wall-of-death mountainside. From up above, it’s remarkable to see the spaghetti bends curling through the green carpet of growth below too. Like yesterday’s track, it’s deteriorating through lack of maintenance. Left as it is, it’ll become impassible again.

We clamber and climb, sweat and plod. There’s almost no metre of the track that’s not uphill. Two thirds of a degree from the Equator we are like indelicate ballerinas caught in a burning follow-spot on an unbelievably massive stage.

It’s one of our hardest hikes, not because of the distance, but because it is relentlessly uphill. From Kabulwo to Salaba is only a little over eight miles – but it is an immense 3480 feet in altitude! It’s exhausting. We start at an altitude of 1160 metres (3806 feet – higher than Snowdon) – and climb a further 3480 feet, which is almost as much as Snowdon. It’s like putting Snowdon on top of Snowdon! And then climbing the upper one…

The effort is worthwhile for the reward of the expansive view of the northern end of the Kerio Valley, looking towards the huge dryness of the Turkana deserts – birthplace of mankind – that is suddenly exposed at the top of the main rise. Unfortunately, there’s a surprise in store though. There are another six kilometres to pant and plod from here to the ‘hanging valley’ road – all uphill.

By now, even William is tired and slowing. I’m struggling. But at last we reach the ‘main road’ – another gravel road snaking across the hills of the here narrow hanging valley. It’s a fine track, one of the finest – I took it a couple of years ago on the Mosquito, a very memorable day’s ride. The African blue sky stretches overhead and as the sun lowers in the west it defines the shapes and contours, its warm light enhancing the colour palette after the bleached quality of the day here, so near the Equator. The shadow of the escarpment slides across the valley floor, away from us up on its western flank.

We hail a boda to take us back to Kessup, ten miles away. Now I can gaze down – from the back of the excruciating hip-cramping boda, and feel satisfied that today I have hiked from that distant valley floor to these dizzy heights.

It IS getting harder, but I’m still bloody-minded enough to do it. A three and a half thousand foot climb in eight miles.

****

That was Friday: an arduous day. To keep the momentum, we hike again next day too. Even William is stiff and weary. He calls for a short day. I’m not disappointed, but I’m glad it’s he who makes the request!

We take a boda to Singore, high up along the escarpment, and walk most of the way home. It’s high altitude but largely downhill or flat. We visit William’s aunt in a rugged timber house on the cliff edge. He grew up here as a child, on the lip of the valley, going to a primary school several hundred feet below. Children play above sheer drops, but no, says William, no child falls off…

On Sunday, our legs loosened by the Saturday walk in Singore Forest, we decide to look for moratina. Of course, moratina is brewed up behind Kessup Forest, 1148 feet ABOVE Kessup…

The forest is cool and inviting, with high old trees, now protected by the government. Behind it, there’s a large cool plantation of conifers, then back to civilisation, Africa style – tin and timber houses surrounded by rough split paling fences, cows, goats and children, calling, “Mzungu! Mzungu!” I must greet and shake a hundred hands. How could I not? But sometimes (today being one) it just gets too much and I want to be anonymous and alone.

Of course, everyone’s friendly when a mzungu arrives, but they’re totally insensitive to my exhaustion after the 1150 foot climb and four miles from Kessup. In the past three days, we’ve walked UP no less than 3937 feet from the great valley! 7750 feet is HIGH! High altitude for one who lives 300 feet above sea level! Leave me to recover, fellows, and I can perhaps join in the joke. Right now, I’m merely so exhausted it’s not funny… Well, in a way it’s no longer funny anyway: I’ve spent almost four months being the butt of a million merry quips and friendly jokes. With the demise of the Mosquito, I’ve had no escape for a few days of reflection.

Bright yellow, I like moratina. With it’s alcohol content – probably about 4% or 5% – it’s popular on Sundays. I begin to relax. And smile at the goodwill.

Moratina is pretty much mead, said to be the oldest alcoholic drink in the world; fermented honey sometimes mixed with herbs or fruit, or in the case of the Kerio Valley, the ash of a tree seedpod. It takes eight kilos of honey to produce the forty litres of drink made in plastic barrels in this stuffy tin hut. Sounds like a huge sacrifice of bee effort, but then, no one here understands that human life can’t exist without bees, or the dangerous state in which they are currently suffering.

We drink our two Coke bottles of livid yellow alcohol, sitting incongruously on a velour settee. The men tell me that women aren’t allowed to drink moratina. I suggest that’s probably because they’re too bloody busy working – while their menfolk booze. They laugh at my idiocy, but the barb doesn’t hit home with anyone…

All the moratina, all forty litres of sunflower yellow sweetness, is gone by 2.30. Just as well we came when we did.

****

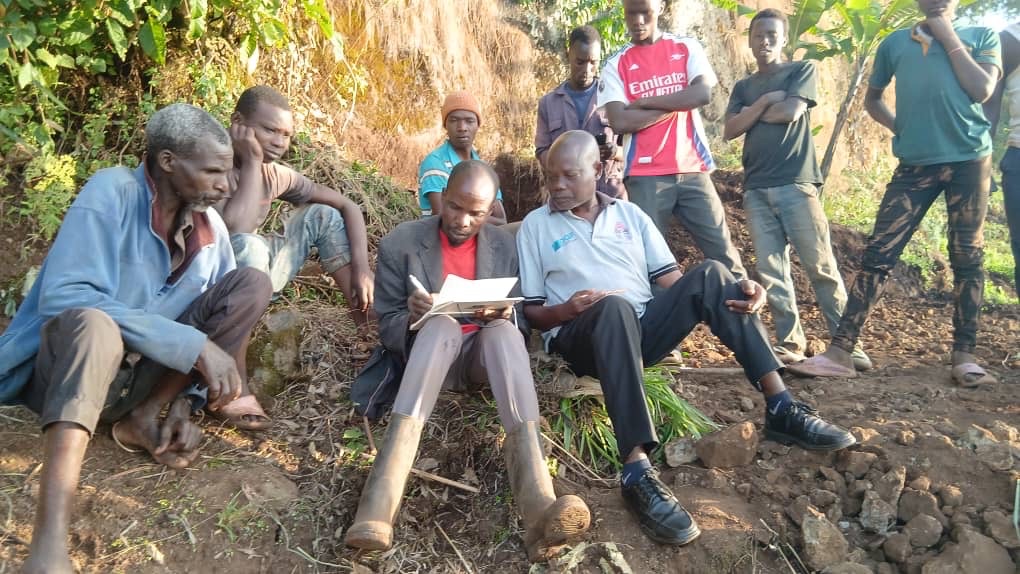

I sleep better that night. Eleven and a half hours. Then I get matatus home to Kitale for the final time this visit. Adelight’s been pursuing her government contract to finish the two-classroom school building. She appears to be in her element, with a team of eight men on site, led by her junior brother, Tito. I can’t help hoping they finish on time and the government doesn’t make its usual delays and prevarications. A big chunk of my savings is involved. At present I technically OWN a lot of those two classrooms! My summer comfort, my lower teeth and hopefully a visit to Devon for Wechiga, all hinge on the government paying up in a timely manner.

Adelight’s team have been making desks for the school in Rico’s garage – from timber cut from the eucalyptus trees in the garden to save money. But this wood is so wet it must be soggy! There’s no such thing as seasoning timber here. One week it’s a tree, the next it’s a school desk, already curling and twisting.

Like most African ‘workers’, they’ve left the garage in a shambles, and walked away: wood shavings, rubbish and food wrappers littered everywhere. The rats’ll love it, and nails scattered on the floor foretells punctures. So Adelight and I turn to and blitz the garage.

I’ve been concerned about the value of Rico’s tools, specialist equipment and valuable instruments collected over a lifetime, now open to pilfering by any people with light fingers and big pockets. So we collect up most of the valuable items and lock them away in the cabinets and office. I drill holes in the cabinets so we can secure them with chains and padlocks.

In the afternoon, it rains heavily for the first time. The rains will now set in seriously. Time to move on.

****

I get the Mosquito running that afternoon. It’s my penultimate day in the highlands. I ride to town then a short ride out along the roads that I know so well now.

I realise that I still enjoy the little Mosquito… It’s perfect for my use: it’s light enough and tall enough that a 76 year old (next time!) can pick it up, and I can dance about on the roughest mountain tracks like a 30 year old. Rico adapted it for my use. He put on his own wide BMW handlebars, a comfortable seat for touring, a strong rack for my pannier bags. We adapted and maintained it for eight years.

A garrulous American missionary has introduced me to a possibly honest mechanic in Eldoret, 40 miles from Kitale. The Suzuki dealer in Nairobi isn’t so optimistic. It seems they too were guessing what the problem may be. “Don’t spend more money!” says the kindly Sikh Suzuki dealer. I have a lightbulb moment! Mano, Rico’s charming 24 year old grandson, whom I met back in December in Kitale, is a biker! And even new parts are half the price in the Netherlands. I’ll ask him to look for secondhand parts. He found me ‘an inspiration’, biking about Africa at my age, he’ll help! Maybe the Mosquito WILL live on..? To be continued…

Next day, I packed up my riding clothes, helmet and boots and put them all back in the big suitcase until next winter. In that action, I am assuming another safari… Well, I can’t face winter in Devon until I really HAVE to!

****

This journey has been all about seeing family, so I couldn’t leave out delightful Scovia and Marion. So, from Nairobi on a damp, grey morning I take a bus to Narok, southwest of the capital, a three hour ride. Up out of Nairobi and down the side of the escarpment, the windows steam up, there’s no view outside either, just a duvet of foggy low cloud. The expansive vista into the valley depth disappears into thick drifting rain cloud. Curio stalls cantilevered out over the abyss are doing no business.

The bus toils down the shelf road into the depths, behind grumbling lorries. A woman yells into her phone, sharing an hour-long argument with some unseen antagonist. Funny how people’s concept of etiquette and privacy has changed with mobile phones. Many seem quite unembarrassed to share their personal thoughts and disputes in loud voices with the world. A woman across the aisle shuts her eyes in Nairobi and goes into what looks like a meditative trance all the way to Narok. I envy her and put in my ear plugs. A child wails and screams behind me, the woman argues on in front. Ear plugs are such a relief. There’s no magic to travelling by public means in Africa. I think with fondness of my motorbike independence.

Narok is the nearest town to the famous Maasai Mara national park. It’s a tidy town, clean, with rare pavements. It’s bright and developing. Scovia, looking terrific in black and white – she’s such a pretty, vivacious young woman – meets me. Actually Adelight’s junior sister, brought up by her and Rico, I called Scovia my favourite African until I knew little Keilah so well. I first met Scovia on her 18th birthday eight years ago. Now she’s mother to Deon, an obstreperous almost-three year old, going through a ‘difficult’ phase. Happily, I’ve had the bright idea of inviting and faring Marion, her sister, to Narok too. Scovia’s husband, Webb, a congenial fellow, a chef for a smart hotel chain, joins us for a brief day off, travelling five hours through two nights to do so. Employment can be hard in Africa.

****

Long journeys bring personal analysis. Actually, it’s a relief to be alone just for a few hours on the way back to Nairobi.

I never say I’m too old for anything, but one concession might be African public transport. I don’t think I have the endless patience I had as a young traveller. It’s funny… it’s my dignity that suffers now. Where did that come from? Dignity? I’ve always been an impecunious traveller – dignity had no place in that. Personal space, respect, status? Maybe I AM finally getting old? Certainly less patient and more crotchety.

And a bus, the back of which is filled with noisy, disrespectful, obviously privileged schoolgirls with the olfactory hint of teenage girls in polyester football strip isn’t easy. I poke in the earplugs and read my book. It’s the only book to be seen. There’s NO habit of reading in most of Africa, with the competition of minuscule attention spans as everyone surfs their phones for stories curated and interpreted by other imaginations. Alex jokes, somewhat ironically, given that HE doesn’t read either, “If you want to hide something in Africa, put it in a book!” How sad that imagination is stultified thus.

I read, buffeted by a 15 year old heavyweight schoolgirl who gossips with all the children around her. She’s pissed off with me because she was sitting in my seat, saying rudely, “You can sit over there!” only to be overruled by the conductor as all seats are full today. It’s a sudden bank holiday – Eid, the end of Ramadan. So buses are busy. She ignores me studiously for four hours. These sons and daughters of rich Africans are the worst: they grow up with a sense of entitlement and superiority in their poorly educated, impoverished homelands, arrogant and belittling their ‘inferiors’.

Across the handsome rolling hills, we reach the base of the huge slope. It’ll be ten miles or more of laborious climbing. And even I could probably outrun the heaving trucks up this long incline, as people overtake perilously, apparently oblivious to the expanding views over the increasing drop to the south: straight down, as much as it matters. Nothing beyond the frail steel barrier to prevent the long plunge from any error of judgement.

I can’t ever quite forget that I have – TWICE – somersaulted through 360° in buses just like this. A rare and unenviable record in my travelling life, I hope. I’m probably the only passenger actually using a seatbelt. No one imagines that big coaches can somersault. On both my previous acrobatic buses, the seatbelts were broken. I have the broken nose to remember the first one, slightly more visible with age, a 51-year battle scar. It’s interesting to think how formative a life experience that first accident was, without the pervasive internet to share my shock and be comforted by words of sympathy. The world was SO big then. I had to deal with shock, broken ribs and a broken nose on my own. And next day, I had to get back in buses and continue on earth shelf roads through terrifying Colombian mountain ranges. On my own. Lugging a rucksack with my broken ribs, a few painkillers from a local hospital my only comfort.

Astonishing that it happened again, some 35 years later! As we tumbled through space, all wheels off the floor, a rainbow of glittering window-glass shards cascading through the air mixed with shiny drops of tropical rain, I remember thinking, ‘Oh no! Not again! Not TWICE’.

I gaze into the abyss beside the road with some discomfort…

****

My dignity affronted, I reach Nairobi. This is no city for any dignity at all! It’s crowded and chaotic with almost no provision for pedestrians, just oversized killer cars driven by entitled men, probably fathers of those rude schoolgirls. It’s no fun walking in this city.

I’m known well at the old fashioned United Kenya Club now. I have my usual rooms and my usual orders. I quite like this familiarity. I hope not too many tourists find this place. Maybe it’s too old fashioned for them. Tonight, people complain how cold it is… It’s 22°!! I’ve asked for a lighter blanket to replace the duvet. Ultimately, I sleep with just the sheet. Room service are shocked.

****

Alex rings to say he’s been planting at Chelel, our newly purchased coffee fields. He’s already started constructing his coffee house and is moving forward in his determined, optimistic fashion, but he says that Keilah burst into tears not to see me at school last Sunday.

****

Adelight WhatsApps to say she’s meeting the inspector to sign off the school work and start the process of payment. Let’s hope the government, not known for straightforward dealing, keeps to their bargain. It’s that or continuing with the bloody temporary denture in my bottom set, I remind her..!

****

William rings to say farewell. “We’ll challenge ourselves to the valley again next year!” he declares cheerfully.

****

Sitting here writing in Nairobi, I wonder about homecoming.

This has been a different trip to any other. I haven’t been my usual peripatetic self. Partly, this was owing to the Mosquito, but also to the interesting fact of my discovery of Family. The strength of commitment to my African families (and I must never forget my closest brother, Wechiga, over in Ghana) has become a defining feature of the latter part of my life. It’s an unbreakable bond. It seems natural to be here now; in some ways THIS is the norm. Going home brings all the familiarity that is comfortable and easy, but so much of my thought and emotion is in Africa now. It’s a surprise how powerful these emotions have become, and this visit has enhanced the closeness.

By tomorrow, when I fly out, I’ll have spent 117 days in Africa. 54 in Sipi, 34 in Kitale and 14 in Kessup. I’ve found a purpose in helping Alex to flourish, in lifting Adelight to independence, and in his small way, William to call himself a ‘dairy farmer’ with pride. The children, especially Keilah, have been a source of the greatest delight. I didn’t expect THAT ‘at my age’.

I am now responsible for the education of Keilah and my namesake, Jonathan Bean. My privilege in being a Baby Boomer gives me a comfortable and relatively easy life. I never really felt the money was mine – and now a good deal of it isn’t! Haha. It’s earmarked for people who have so much less access to our comforts and financial security. It seems fair to me.

****

Yesterday… Alex called to say he’d been offered half the plot next to our Chelel coffee field! He’s agreed to purchase! It’s a good bargain: just 4,000,000 Uganda Shillings – about £900. His neighbour needs to raise money for two children to sit their National Exams, and like almost every Ugandan, has too many children and lives for the day, not realising that once sold, he can’t profit from his land again.

I can only chip in £250 today; Adelight has the rest! Somehow, my determined young friend, as close to a son as I’ve got, raises the rest. Who knows how? It’s that truly African mystery… He’s a man of property. In Africa, there is no more valuable asset. I’m very deeply proud of him.

I fly out late tomorrow night. The forecast for Harberton is for full sunshine for the weekend. I had a feeling my extra month might pay off, after the misery of returning to dull rain and darkness last March. The clocks have gone forward. Everyone will look at me, tell me how very fit I look and tell me I’ve brought the sunshine from Africa.

I think ‘Sunshine’ is what I feel too…

Thank you for reading my blog. I hope it’s informed and opened your heart to Africa. For me, as must be obvious, there’s nowhere like these countries on this always surprising continent…

JB 2 April 2025