EPISODE THREE – January 31st

For some inexplicable bureaucratic reason, I can stay in Uganda until the end of my visa in March, but my motorbike is only allowed in for 14 days without paying a £50 tax.

So here I am back in Kenya…

****

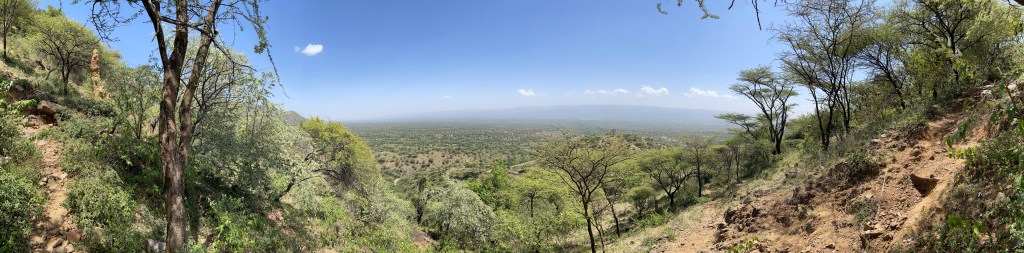

If the middle part of the ride between Sipi and Kitale wasn’t one of Africa’s finest rides, I’d be rather bored by it by now. Fortunately, the slopes of Mount Elgon and the swooping Chinese road combine to make it a special journey. The views to the north are magnificent; the engineering – perhaps especially because I first knew it as little more than a chaotic footpath – combine to make this a memorable ride. My road is twenty yards wide and still in good condition. I can choose my riding line on a whim, it’s so devoid of traffic. I’m so well known at the border that I can cross in minutes.

“Do you know where you are going?” asks the immigration officer in the empty echoing halls of the ridiculous Chinese-built border post, “…Exactly?”

“Yes, I’ve been this way many times.”

“Well, you can’t use GPS! There’s no internet.”

Biting back the retort that I was born fifty years before GPS was even thought of, and mankind has found its way for tens of thousands of years without it, I assure him I’ll be able to find my way.

With a ridiculous ‘election’ tomorrow, a purely hubristic exercise on behalf of the inevitable winning party – there being no chance of any other outcome – the president has demanded that all internet services are switched off for the next days. Such is the power of despots (watch out USA). It means that all banks must close, hospitals, communications and most services will be disrupted. Recent events in Tanzania in which people died during election protests assures the ancient president of an excuse to take draconian action. As if he needed an excuse.

****

My ‘grandchildren’ jump up and down in excitement as I ride down the track to Rock Gardens at the end of my journey. Alex is hurrying from Chelel, having asked Precious on the phone, “Has my father arrived yet?” I feel at home.

For the next several days, I’m engaged in putting chain link security fencing around the guesthouse. Digging soil here is like mining plastic: crushed single-use bottles, countless thin black bags, sachets, wrappings, broken plastic plates, plastic shoes that lasted only days. The filth is painful to see. And how old is plastic as a material? About seventy years? Yet all the world is thus thickly polluted. There’s no rubbish collection in Africa.

I take charge of the cheerful, fun teenagers: Charles, Rach and Ryan, and we erect the fence to Rock Gardens, fun days with the young men. I do like to be around young people – and here in Uganda it’s pretty impossible to avoid them! These boys are polite, thoughtful, respectful and endlessly full of life and jokes, while including me as a sort of equal too.

Seven days of chain link fencing, with sore hands and punctures and scratches all over legs and arms; working with sharp wire, rusty barbed wire and no proper tools except small pliers from my Mosquito toolkit is trying. For cutting, no saw, just a panga (machete). For drilling, just a six inch nail (bent). For nailing, an twisted broken hammer with a welded handle that transmits every blow. For digging, only a hoe – if the bloody neighbours haven’t taken it.

Joshua, a guide and helper at Rock Gardens, overhears someone say, “Alex has his own engineer! It’s a mzungu!”

“Ha!” laughs Alex, “Don’t joke with me. I can even employ a mzungu!”

****

But there are frustrations too. This village is poorly educated and many wish Alex ill for his success. Some even use ‘African Magic’ to try to bring him down – but that only works if you believe it…

The trouble starts when it’s reported that Alex is enclosing his compound. Perceived as rich, it’s seen as an opportunity to attempt for some quick money. First the neighbour to the side objects that the outward angling tops of the concrete posts have taken a few inches of his land, on which, he says, he’s going to build. Alex must pay compensation. He’ll never build. Instead, we remove the poles and turn them round. Frustrating, but somehow satisfying.

Then, the neighbours at the bottom of the plot see opportunities to extort money and claim that we’ve encroached onto their land by eight inches. This discussion brings the father, a fat, ill-tempered drunkard, who’s abandoned his family for drink (the African problem). He claims two million shillings (£400!) for our encroachment. Angry discussions continue, the gleam of money-for-nothing in their eyes. Eventually, 300,000UGX (£65) is decided upon.

“I won’t pay the bastard even a glass of gin! Not ONE shilling!” I tell Alex angrily. The land in contention wouldn’t even grow a row of potatoes, even if the man tilled his land, which he doesn’t. We undo our day’s work and move the poles back out of sheer but satisfying spite!

I must remember they don’t represent cheerful Uganda, just this village that so much resents Alex’s success – although he buys their produce, chickens and goat meat and brings tourist money to their village. Lack of education in this derelict country is a sad fact. Fortunately, It’s a very local phenomenon to the village where Alex was born, who cannot bear to see one of their own progress, while they stagnate through lack of effort.

****

Happily, the Chelel villagers aren’t like this.

Chelel is where our future project is slowly maturing into coffee plantations and the next hotel: the Chelel Starlight Hotel on its wonderful mountain terraces. Here, we meet friendly people, thrilled to have a mzungu investing in their area for the development they hope it will bring. We receive gifts of local honey and a big heads of matoke (the savoury banana staple). They put the local Sipi village to shame. Back in Rock Gardens, everything has its price, even to having to buy old newspapers when we built the earth oven – and accusations of ‘stealing’ a few inches of land!

****

Fortunately, Chelel is where my pension+ has gone in the past year. A future for my Ugandan family.

I never felt the paternal urge, and I couldn’t have lived the life I have with a family to care for. I doubt I could have borne the restrictions on my liberty and self-reliance anyway; I’ve protected that to an almost absurd degree and lived life very much on my own terms, without many compromises.

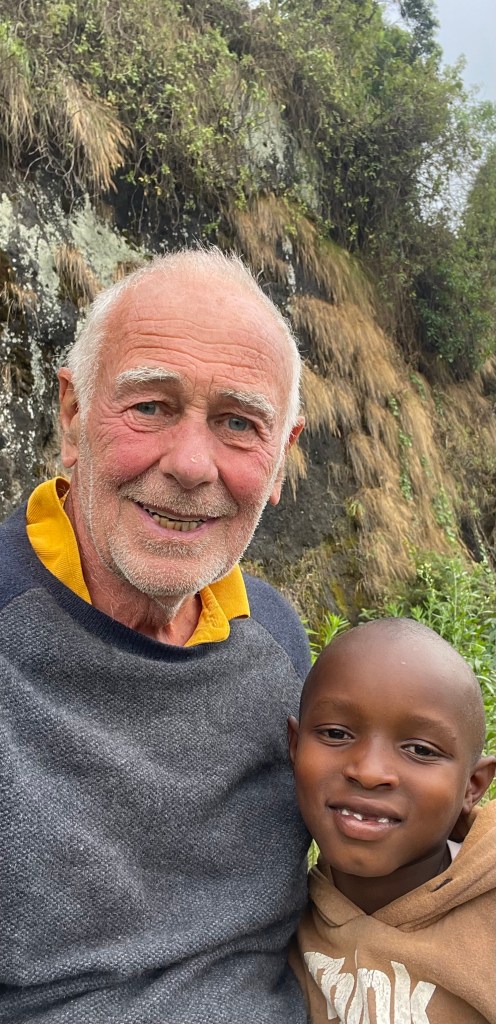

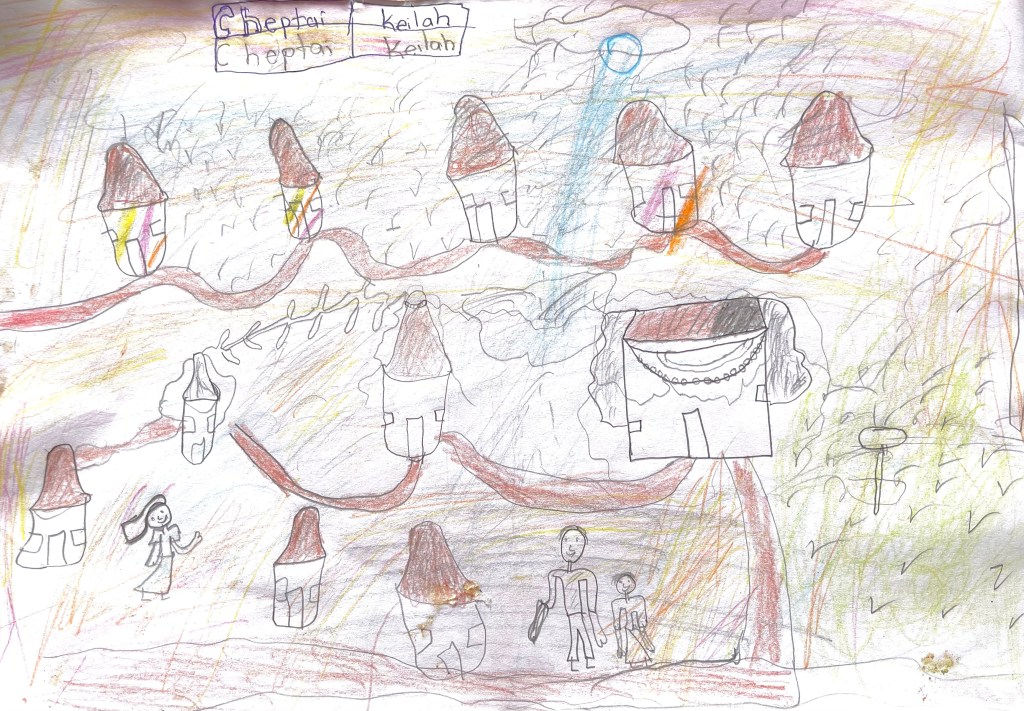

So it comes as a big surprise to find how much I have come to love two small brown African children! I find I have the infinite patience required to be in the company of a seven year old boy, full of questions and limitless energy, and an affectionate, increasingly smart, questioning nine year old girl. Both JB and Keilah are benefitting by their exposure to so many people of different Western and African cultures at Rock Gardens, and live a life not dissimilar to that of my own childhood – from a now very different age. There are few ‘sophistications’ and very little access to ‘devices’ that limit imagination. They have an active life filled with familial duties and small adventures; allowed to take risks – perhaps the most ‘natural’ existence and growing process any child is allowed today. They play imaginatively, despite their many privations of situation, and it’s an enviable childhood I think.

Jonathan and Keilah will grow with ideas of their own, rather than influence from the manipulative control of other agendas. I can see a growing natural wisdom in these two children: Keilah is already forming her own independence of opinion and character, and JB will follow fast, as they are intelligent children. Perhaps their biggest benefit is to be just two children, close to one another, playing generously together without dispute and sharing happily. They haven’t 6, 12 or 13 siblings – or even 64 by one father and ten women, the most prolific producer I have heard of in this baby-factory of a nation. They have an intelligent father and a caring family situation. They go to a good school, which they love, and are well fed and healthy – things impossible to guarantee in this country where education is rudimentary at best, and health a matter of chance and money; where no one has been taught to plan for tomorrow, let alone future years – and half the population of 50 million is less than 14 years old.

Keilah and JB do household chores, play endlessly and proudly look after the five cows or go walking with us, which often turns into a nature study walk. They’ve had hours and hours of fun with colouring books and pencils, creating images from their imaginations.

****

I’m not ‘rich’ in many people’s terms, but I did sell my Yorkshire house for 34 times more than I bought my first property 30 years earlier; a short-term madness that’s preventing so many from enjoying wealth in the future. A few years ago, my wise financial adviser (and I NEVER thought I’d have one of those!) gave me the best (and most surprising) advice: “Jonathan, I think it’s time you started giving the money away. Your African families are important to you. You’ll have much more fun watching those families progress, than waiting until you’re dead.”

We Baby Boomers, we’ve had embarrassing riches to enjoy… Not only have we had the ridiculous change of economic values that brought us the ‘Housing Boom’ with, for some of us, the lessons learned from the DIY revolution that kicked in during the privations of our parents after the war. We may be one of the wealthiest generations, in all senses. We’ve lived at the start of the destruction of all that maintains life, rather than suffering the consequences that are coming. We’ve had all the advances of science and social welfare reforms, now being stripped bare by selfish, prejudiced rightwing politics; we’ve enjoyed freedom to do things our way; we had optimism in our youth that we were going to change the world (although, in the end, we changed only ourselves…). We’ll probably be one of the longest-lived generations, growing up before the industrialisation of our diet and ‘playing out’ as children.

The pleasure I am getting from my advisor’s advice is immeasurable. We’ve created Rock Gardens together, Alex my ‘son’ and I. Now there’s the coffee plantations and Chelel hotel. The children are at the best school available (rated 17th in Uganda). Adelight is gaining independence in Kitale, assuring me that her next government contract is almost assured, thanks to my loan last year, (now half repaid). William counts himself a ‘dairy farmer’, with his three Holstein cows, and is becoming modestly self reliant. I’ve given modest interest-free loans to other family members to invest in their future, and over many years I’ve been able to give support to my Ghanaian family as well, and help for medical and family emergencies.

In my world travels, so many strangers have shown me TRUE generosity. The most generous are those who give what they can ill afford: food they would eat themselves but that humanity and culture insisted they gave to me; they’ve opened their homes and hearts. It’s a lesson I’ve not forgotten.

****

Last week, I bought another acre or two of Ugandan mountainside in Chelel. It has an even better view, but I’ve told Alex, no more building! I’ll allow him a small thatched shelter under which his guests can drink coffee or beer and enjoy the view of the vast yawning valley that stretches to infinity, but now it’s time to invest his effort in getting the farming business up and running.

Meanwhile, the new hotel continues to grow. Moses, the best worker, is digging foundations for the kitchen and restaurant. Local boys are laboriously hoeing acres of land to plant more coffee seedlings and ‘Irish’, as potatoes are known in Uganda. There’ll be onion fields, passion fruits and local vegetables that will help to make Rock Gardens and the Chelel hotel self-sufficient.

Alex is already bringing work to Chelel villagers. And they support him happily.

****

Travelling is frequently tedious, uninspiring and trying, but there are days that make up for all that. I guess life is always like that: a few highs worth waiting and working for…

Alex and I keep on hiking for relaxation. With the delightful, laughing company of the young men, Charles and Ryan (18) and Isaac (13), Alex, little Jonathan and I hike about 15 miles with punishing ascents and descents, stairways, ladders and clambering up mountainsides, all ending, long after dark, with the usual eight hundred foot clamber up to Sipi.

By the time we stagger back into Rock Gardens, long after dark at 8.30, we are exhausted from an accumulative climb of perhaps three and a half or four thousand feet and the altitude: never less than 4600 feet, topping out at 6450. We’ve clambered ladders and slithered down dusty rocks and climbed rocky volcanic slopes, scrabbled through vegetation and stumbled through matoke plantations and miles of coffee bushes in this magnificent countryside.

We’ve met hundreds of people; been called to excitedly by thousands of children; we’ve been disturbed by hoards of noisy election crowds clamouring for the pennies handed out by agents for local candidates (as little as 20 pence buys a five-year lucrative office for these corrupt officials).

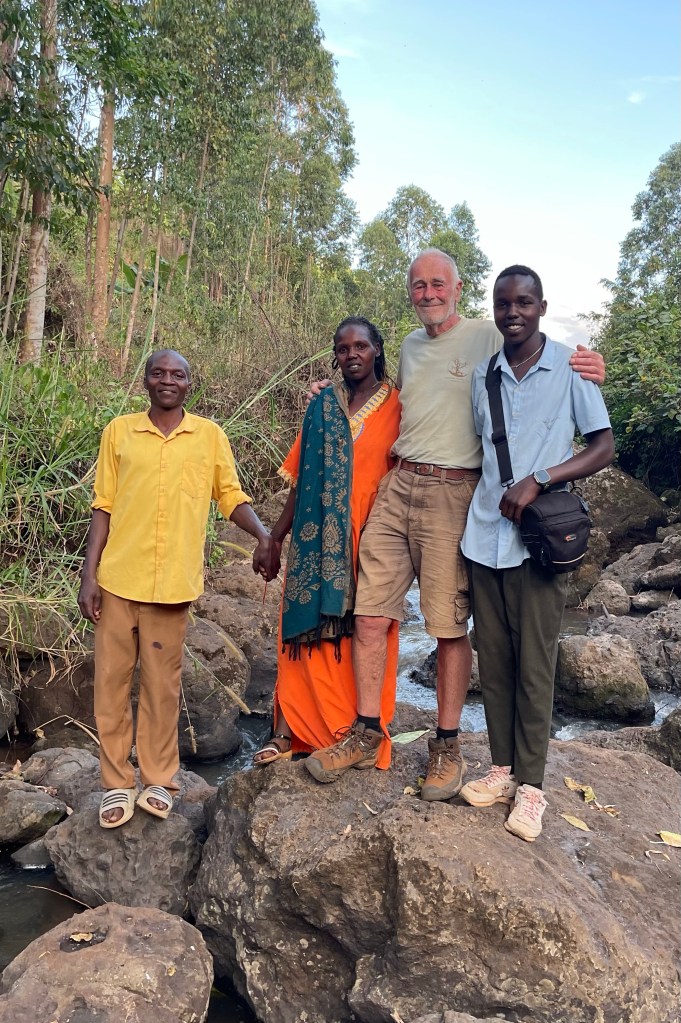

Tea and chapatis in a scruffy village and then those punishing 946 stone steps, back up 650 feet to the heights. After that, a rising and falling wander through forests and coffee bushes with the yawning gulf alarmingly close, slipping away sharply from our grassy path. No place for those without a head for heights or of suicidal tendencies – or the drunkards who sometimes go over the edge. On a clifftop above a slender spray of a waterfall, that shimmers down 200 feet, we find a pool in which the boys frolic noisily. Then the two long steel ladders Alex and I have used several times to descend to his sister Doreen and husband Leonard’s compound far, far below.

We are welcomed warmly, with thick fresh chapatis and eggs – you can’t visit family without food and drink, even when the sun is slipping down the western sky and you still have four miles to walk and 1000 feet to climb. Leonard’s coffee must be ground in a mortar, roasted and prepared. By now I’m watching the orange sun sinking and glad I brought my torch.

Happily, Leonard knows a short cut. It proves to be a mile of coffee shambas and farmland, dotted as everywhere in this vastly overcrowded country with mud and earth homes with corrugated roofs. We must stop to greet the householders. Judging by reactions, it’s likely I’m the first mzungu to go this way.

Leonard and Doreen leave us at a dust road. We put little Jonathan and Isaac on a boda-boda as dusk sets in. They’ve walked at least ten or eleven miles. Now Alex is concerned for my safety. Unlike my companions, I can’t see in the dark, but I am determined to complete the hike.

In one village, as darkness falls, I am followed by a huge gang of children and youths, pretending to be a bodyguard for the mzungu election candidate. By now, I am getting beyond being the endless, day long – Africa-long – joke: “EH! MZUNGU!” from every corner, as I concentrate to see where I’m putting my feet on the now dark, dusty road. We finally stumble up the 800 foot escarpment, only Ryan’s light shorts visible as I flounder upwards in starlight, the sky filled with diamonds.

The best feature of my day is the company of the young men; Isaac, with his perpetual happy grin, and JB2 with his boundless energy. They make the day special. It’s so good to be around young people.

****

Alex and I have been long concerned about the fast growing pine in the middle of the guesthouse compound. It’s immensely heavy, slender, tall and shallow-rooted. If it falls in the evening winds that blow up from the plains far below, or gets struck by lightning again, it will demolish all – and anyone – beneath its trajectory. Reluctantly, we decide it must be felled.

Watching a 72 foot pine being trimmed to a bare trunk by a fellow with bare feet and a panga, and then felled by a man in flip-flops with a two foot chain saw, is an anxious activity for a Northerner. Later, the trunk is cut into one inch boards with the same chain saw, by a man in a tee shirt, with no eye protection, gloves, hard hat or ear defenders – let alone SHOES. It makes even me wince. Life is cheap in Uganda, and safety not considered. Perhaps such poor education causes a total lack of imagination? It’s the same with boda riding, 240 volt electrics, sharp tools, fire, construction work – every potentially hazardous activity: a fatalistic belief (or lack of imagination) that nothing will go wrong. A man, 60 feet up a swaying pine trunk, with no safety rope or protective gear whatsoever, wielding a panga… God’s will is in control, maybe?

****

In a week’s time, I fly from Nairobi across to Ghana for 23 days. Ghana, my first and longest African influence; my 22nd visit. Where and when I’ll find internet, I’ve no idea. I do know it’ll be the hottest month of the year, a decision I made to make the most of the school holidays of Keilah and little ‘Bean’ in Uganda.