IT’S TOUGH, AFRICA

6th JANUARY 2025

Grandfatherly duties take a lot of time, hence the long gap in my updates. Well, they’re not duties of course: they are pleasures; pleasures I never really expected to enjoy until I gained my two surrogate grandchildren in my ‘old’ age. A great gift.

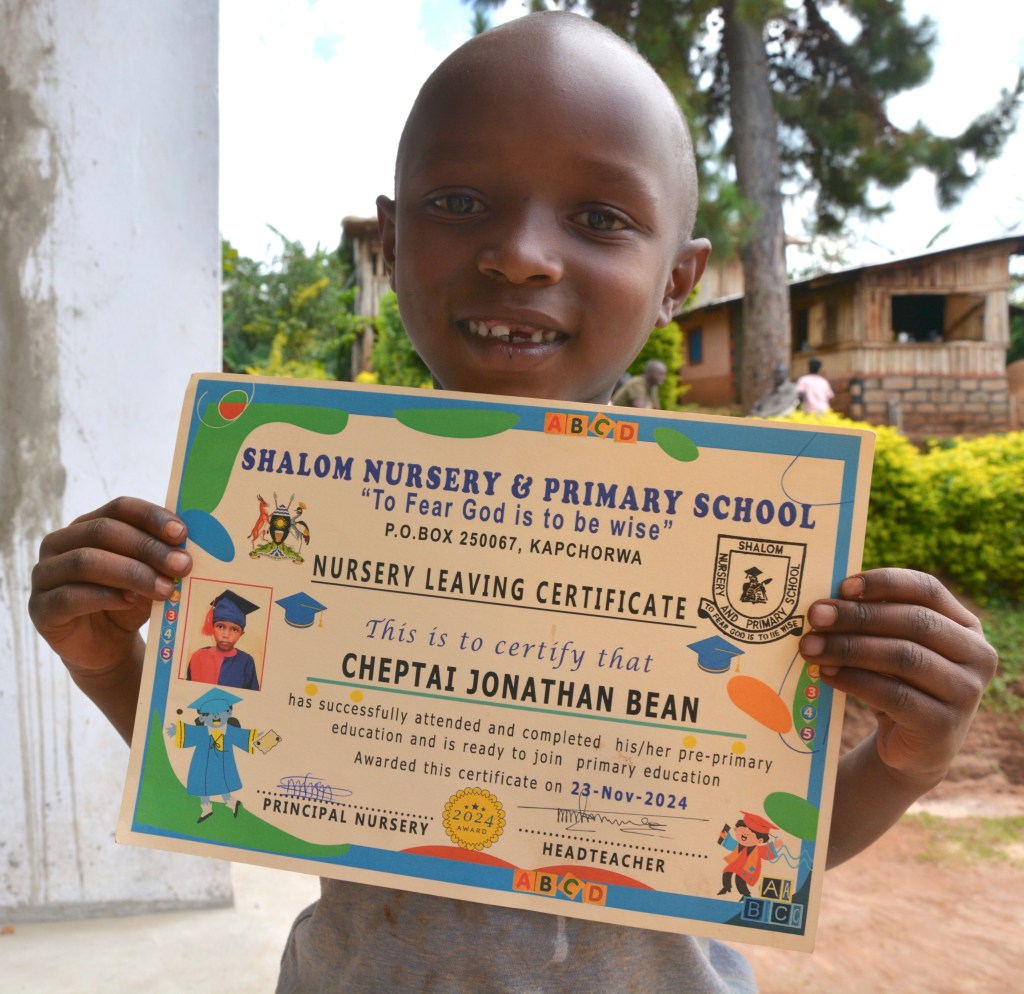

My favourite African, charming little Keilah, eight years old, is a warm-hearted, unsophisticated but intelligent little girl. We rather love each other! Jonathan Bean is a boisterous fellow, just turned six years and full of life. He copies most of Keilah’s actions and they entertain one another happily, with few spats or battles, perhaps thanks to Keilah’s patient nature. They join in the household activity, as most African children do in a culture without ‘labour saving’ devices. Washing all the guest house bedsheets is a constant chore carried out in the garden in plastic bowls; cooking is over smoky open fires or charcoal; cleaning is with hand-brushes and cloths. Ask the children what they’ve been doing, and the response is invariably, “Sweeping…”

Now they are growing I don’t get wakened at their whim, but they watch for the door of my house opening, my signal that I’m ready for my morning hug and greetings. We breakfast together up in the crazy wooden restaurant, product of Alex’s imagination, all formed from wooden poles, elevated ten feet above the compound, decorated by me with line drawings in mud paint of local activities and scenes. I’ve come to love these two children – and perhaps I’m at a time of life to fully appreciate the joys of having small children around. I never felt the paternal instinct – too restless and free spirited for that, but I DO like children and finding two such delights now is a great joy. But they do demand attention that prevents the peace to sit and write…

****

I rode round the mountain on December 28th, now a fine quick ride on the sweeping Chinese road. It’s twenty yards wide and empty of traffic, except local boda-boda motorbike taxis and a few labouring local trucks. Why the Ugandan government has elected to build this expensive folly, and the extravagantly vast ‘One-Stop’ border post (built by the Chinese State Construction Corporation…), is impossible to understand. No articulated trucks, the traffic that blocks the lower altitude border posts between Kenya and Uganda, is likely to opt to drive over these high mountain shoulders, with steep inclines and curving tarmac. And few tourists come this way to be impressed by the hubris of the ‘One-Stop’ border post, another source of immense debt to the rapacious Chinese government’s economic colonisation scheme. In lieu of debt repayment, China last year seized ownership of Entebbe Airport, Uganda’s state airport. (They tried to get Nairobi’s airport last year, but the Kenyans united in objection…) China does nothing for free, and the president is well entrenched in their pockets. Poor Africa. The British stole their resources for 150 years; the Americans imposed their hideous cultural colonialism; then the Chinese milk what’s left, providing apparently cheap loans that come with vast cost – repaid in land grabs of mineral-rich untapped mountains and deserts and natural resources.

The unhurried border officials recognise me now. My passage, with my hard-fought six month multiple entry visa causes a little consternation to Betty, the immigration officer, who has to consult her superior, but is apologetic for the delay. Business is still done by the same few officers in what appear to be huge garages; there’s been no progress with the giant architectural folly since March. Priorities are perhaps best proven by the only large poster in the Kenyan immigration offices: ‘8-ball English Pool Official Rules’. The pool table has been the centre of activity for the seven years I’ve been coming this way, since the days of the broken gate, the dust-covered tin huts, the concrete colonial bridge from 1956, and the rutted goat track across the rugged mountains. This time, I arrive at lunchtime and must wait upon the immigration officer’s whim.

****

The views to the north feel as if I am gazing over half Uganda. Small pimples of extinct volcanoes prick the blue-hazed distance. I lean and bend; this is one if my favourite roads as it weaves its way along the mountainsides. It’s difficult to remember just how hard this road was four years back, a deep dusty, rocky rutted track – that was SUCH fun to ride on my small trail bike, 90 miles of exhilarating riding. Now it’s smooth and boring, but quick. I’m reminded very soon just how outgoing Ugandans are, as children scream from the steep banks and adults stare from their doors of tin-roofed, earth-built houses at the roadside. It’s fun to ride in Uganda.

****

Then I’m at Rock Gardens for the welcome the children have anticipated for so long. Precious is ululating, the children clamouring. Alex is away at a clan function, elected MC yet again, this wise, smart young man.

There are new buildings everywhere. This is where my money’s gone since March. Most of ten grand of it. Two new round houses with grass roofs (over metal sheets for the abundant rainy season), a new gate and gate house, a raised wooden terrace that stands higher than the hedges, and an ugly sort of bungalow block, imposed amongst the ‘traditional’ round houses.

It’s a mistake, I see immediately, out of proportion and angular, like something dropped in from a housing estate in Kampala, amongst our quaint structures. When Alex comes, he tells me he had to build it as Ugandan guests are too proud to sleep in our old fashioned African heritage rooms! Its ironic that he has to pander to pride here.

Rock Gardens is still the cheapest accommodation in Sipi, getting the highest ratings on the internet, popular and well booked. Travellers now use the multinational corporations to book their rooms; gone is the fabulous serendipity of going and looking for yourself. It’s in Alex’s favour, but I regret that so many young travellers have such a tame experience nowadays; it’s taken the adventure out of travelling. Even backpackers book ahead now, book guides, do the same activities as everyone else. It’s bland and lacks the initiative we older travellers required. Now they sit on their phones and ‘share’ it all with their friends at home, instead of being in the moment – in Africa. Well, times change I suppose and mine is only the bleat of all the old about the young…

****

We decide to remove the bungalow roof and redesign it: it’s far too dominant. As I write, the appalling workers are demolishing the zinc roof. Every construction job in Sipi is done with no more than a hammer, a panga (machete) and a hoe. Hammers have long lost their handles, replaced with odd bits of welded pipes; pangas are shortened by use and the hoes have rough sticks for handles. I lose my rag many times a day. Why not buy some simple tools? A chisel to separate bricks instead of a battered hammer: we might save the bricks. A jemmy, surely no more expensive than a couple of pounds here, to lever the timbers apart. They’re all nailed anyway: you can’t even BUY a screw here. Instead of a small outlay, they waste huge amounts of energy, doing things the difficult way. I’ve stopped buying any tools and bringing them from better supplied Kenya – they all get stolen within a week, or are destroyed by lack of care. One day, I ask for the spirit level. I bought it last year. Now it’s blathered in old cement, with its level missing and shaft bent. I have to throw it away. “Oh, do it your own bloody way!” I just yelled at Tom, the worst wood butcher I know. I have to walk away.

****

In October, two electric poles fell down up the muddy lane to Rock Gardens and its village area. A young woman died. It’s a common death here. Five people have been buried from deaths by electric shock in the past months. I’m not surprised. There’s a flagrant disregard for the dangers of 240 volts, where wires are knotted and bare, poked into sockets with sticks, and left in uninsulated twists, open to all. Right now they’re burying another victim down below Rock Gardens.

So Alex (me!) invested in a generator. It’s making a hell of a racket and something is very wrong. Even I, lousy mechanic that I am, can tell. When I investigate, I find that someone – ‘who knew the answer’ and fiddled, has stripped the thread on the spark plug housing. There’s no plug cap anyway, just a twist of HT lead. I forbid Alex from letting ANYONE else even touch the machine.

“Ring Kato now!” I demand, knowing that Kato, the mechanic that now looks after my Mosquito has more skills than any of the ‘mechanics’ in Sipi. He rides down from Kapchorwa, the town 17 kilometres back up the road. In twenty minus he confidently strips the machine. It needs a new cylinder head, the barrel requires reboring, so a new piston and rings; the silencer needs welding up where it is shattered right round. The valves need decoking and adjusting, the armature is covered in oil and the brushes knackered. It’s so far out of tune it’s amazing it runs at all. Most nuts are stripped and rounded.

It cost over £200. Sipi’s ‘experts’ have destroyed it already. It costs me £80 for Kato to get it working again.

It’s TWO MONTHS old.

****

Alex is stressed much of the time. It’s so difficult to run a guest house for so many strangers in an ill-supplied place like this. The state electricity probably won’t be repaired for years, and only then when there’s a big enough bribe to some official. On January 1st, the water supply mysteriously goes off. We spend the morning carrying water in 20 litre jerrycans up the hill from the spring, 100 feet down the hill. I make three trips: 60 litres. Water for guests who have no idea what it’s like to live without a tap to dispense purified water. We suspect that the minor ‘official’ in charge of this area supply has turned it off to get bribes to reinstate the supply on this public holiday. But everyone spends hours of labour trudging up and down the hill. The water comes back just as mysteriously at midnight. The water official is also the local ‘plumber’, moonlighting. He’s installed a lavatory in the new ugly room. “It doesn’t flush…” says Alex, “and there’s something wrong about the seat.” The ‘plumber’ left without adjusting the plunger on top, and fitted the seat brackets backwards, took his money and left. He hoped Alex would call him back and pay him to ‘repair’ his workmanship. He didn’t bargain on a practical mzungu!

But it’s this way all the time here: lazy, uneducated and backward. This clan, Alex admits, is known for its jealousy. They look at him progressing, and rather than cashing in and gaining from the tourists he’s attracting – setting up small kiosks with their produce, making handicrafts or souvenirs, getting together to put on cultural displays – they undermine his business. The local expensive hotel set up a scam to deplete his reputation: they got a young woman tourist to come to Rock Gardens, pleading poverty and needing a cheap deal. Alex is generous about this. “She kept herself to herself,” he says. “She didn’t come out of her room, and she couldn’t afford to eat!” Next day, she claimed that $500 had been stolen from her room. To avoid damage to the reputation of his business, Alex had to pay up. “I think she wanted her fare home,” he says with an ironic smile. “Even the police, so corrupt themselves, suspected it!” Later, he found that he had been set up by a jealous local hotel.

Locals constantly tear down his guest house signs, and have thrown stones through guests’ car windows. They break and steal out of jealousy. They ‘steal’ his guests, taking them elsewhere. He began to get bad reviews from guests who never even came to Rock Gardens, redirected to inferior places by his local ‘agents and guides’, forcing him to close his account with the horrid multinational booking company we all know but I can’t write without importing links to your device as you read. He sacked his ‘guides’, lost all fine reviews he had, and had to start again.

Scratch the surface of rural Africa and you see the truths hidden beneath. But where, in a country like this, is there an example of selfless decency? It’s corrupt and amoral from the very top to bottom. The president’s wife is minister of education and sport, his daughter head of the national bank, his son head of the army and president in waiting. Every official and politician is utterly corrupt. Nothing happens without greasing the wheels.

There is no example. Immorality spreads, especially amongst the misogynistic males. Rape and unwanted pregnancy is astronomically high: “Probably 85 percent of families in this village have had unwanted pregnancies amongst their daughters. Many of them schoolgirls!” Last year there was a revolting crime committed in this village. Two teenage girls, one of them with learning disabilities, were given the choice by a gang of drunken boys: either be thrown over the 200 foot high cliffs or be gang raped. The boys fled across the country but, Alex tells me, the father is a rich man and had the resources to insist that the police did not give up. Some boys were caught as far as the border to Rwanda. Several are now on remand, and may spend years in prison. But it was the father’s wealth that made for a measure of justice, not moral indignation. “The community kept quiet…”

****

Recently, Alex ‘rescued’ Josephine, left pregnant by a married boda rider, who subsequently threatened violence. She was rejected by her family; tried abortion herbs unsuccessfully; considered suicide. Alex employed her at Rock Gardens, a reserved woman with a gentle smile once she’s comfortable. This week, a baby boy was born in the hospital (another bloody Ugandan man in the making) and after two nights she came home. I can now add £100 ‘birth fees’ amongst my very varied expenditures in Africa, way beyond Josephine’s resources. Alex was going to pay, from his small profits.

Alex tells me about his latest ambition: to construct a sheltered haven for all these young women left with unsupported babies by irresponsible men – the ‘85% of local families’. He already completed a rough hall on a plot of land a few hundred yards away. He hopes to be able to provide a safe place where these often rejected girls and women can gather to share their lives and fears, perhaps to find mutual support to care for their babies and find some way to support themselves. He plans to set it up as a small local business and hopes for support from visitors and donors. He’s a determined young man with a strong social conscience. I will support him of course…

****

In Kapchorwa, 17 kilometres by road, where we’ve walked over the shoulders of the great mountain, probably 20 kilometres, with Sarah, a visitor from Germany, Alex introduces me to an age-mate, 74. As he leaves, Alex tells me, “He has 46 children! From six women.” Poor Alex, who volunteers to try to reduce the birth rate, increase education for girls, stop female genital mutilation. Men with whom we are sitting, laugh at my anger. They don’t understand anything but that he is a ‘strong’ man. I bet he can’t even remember the names of the average eight children of each woman.

This baby factory of Uganda undermines any hope of continued human life on this planet over coming centuries. Over seven children is the average per woman, most families include children by ‘outside’ women. Rape is endemic. Uganda has grown from 5 million to 50 million in my lifetime. The growth is exponential, rising to 100 million by the end of the century. Resources of land stay the same. Pollution increases. Food quality reduces. Education is low. Morality elusive. Good example rare.

But the Bible and Koran both, “Tell us to have babies…” No one understands the pressure on the planet’s resources. “God will hep us if we pray…”

****

At Rock Gardens, we have varied visitors, most of them very congenial. Interesting folk from all over the world, the exposure for Precious and the children is terrific. Precious, now 29, has matured a lot, gathering liberal opinions from the many young people who stay. She now accepts that two children gives her family a chance to develop, be well educated and remain healthy, a fact that most rural Ugandans fail to grasp.

****

Walking down below the steep cliffs, accessed by dramatic ladders, we stop at a simple house amongst the matoke banana trees. I’m known here and the welcome is fulsome. Alex and I are with two smart, open minded Dutch young people, Rosa and Vincent. Two small girls are fascinated by Rosa’s long light-coloured hair. She’s a good traveller, patient. They stroke and play with her hair for half an hour. Miracle is a thin girl in a black leotard, cropped hair and a shy smile. Her friend and mentor is Elizabeth, a very bright girl of about eleven, I guess. (I can seldom guess ages as African children are usually so much smaller than Europeans). “What’s your ambition?” asks Alex, always quick to engage children in conversation.

Quick as a flash come the retort, “I want to be a lawyer!” We are all impressed by her certainty. She has an educated father, who’s a local small-time politician and clan leader, so perhaps she has a chance in this misogynistic society. “What do you think are the obstacles?” asks Alex.

“Ignorance of parents and the attitude of men,” Elizabeth replies confidently. We all praise her determination and encourage her. It’s always good – and sadly rare – to find girls and young women with confidence here.

****

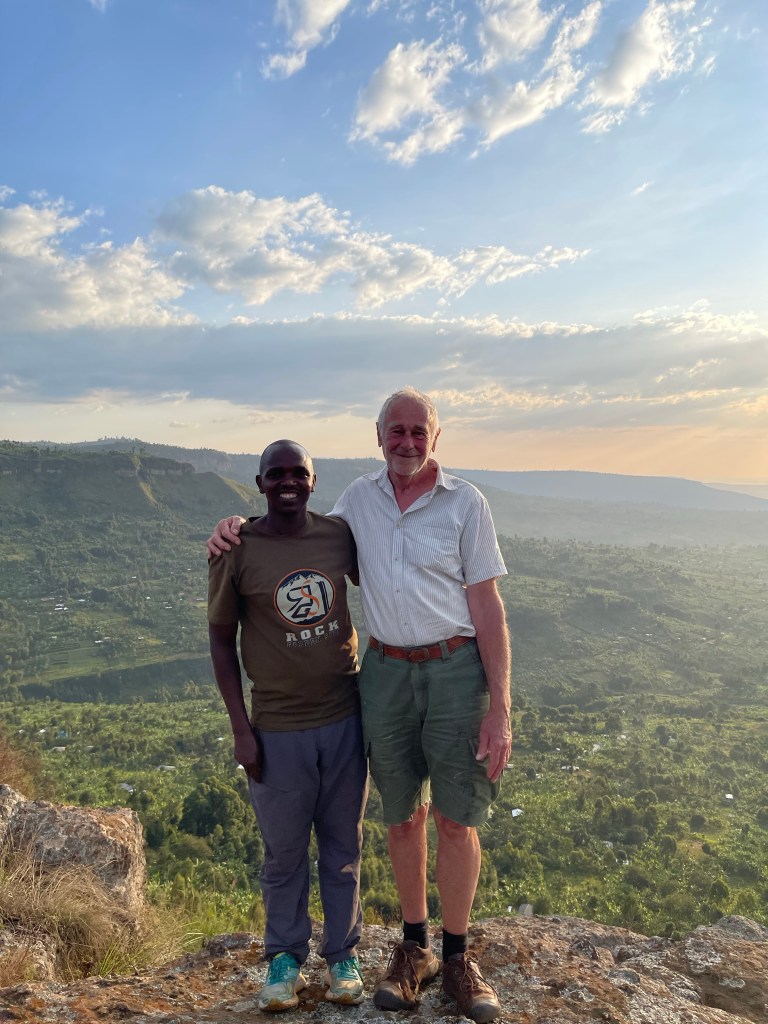

Thank goodness we have our hikes to get us away from the frustrations and irritations of local rural life, its jealousies and hatred. Alex is a great companion. He gets no support from his own family, despite being the firstborn so I’ve taken on the role of father-figure.

We have some long hikes we like, and are always looking to extend our repertoire. One day, we walk to ‘town’, Kapchorwa, a hike that he does frequently now, maybe 20 kilometres. We hiked it together for the first time three years ago. It’s varied country, dipping into the Mount Elgon national park with its old mature trees and birdlife. We cross streams, struggle up loooong hills of grass and colourful equatorial scrub. We climb to some high bluffs that Alex calls, ‘Jonathan’s Point’. There are vistas all around, green valleys with swishing banana trees, tall conifers, and winking tin roofs. Red dust roads wind around the contortions of the steep hills. The extensive plains far below fade to the horizon.

We relax and unwind. Here and there, our routes have a frisson of excitement as we must clamber ladders, some made of steel and others of rickety timbers nailed to tree trunks leaning on the cliffside.

One day, we take Keilah and Jonathan up that crazy ladder. They love it! With no fear, Jonathan shins up the steep rungs, laughing in excitement. Both children, followed by their father, wave down at Uncle Jonathan 70 feet below. Uncle J ponders how we overprotect our Western children from all dangers and risks, limiting their the opportunities for such adventures. As we climb into the gulley at the top, two small girls – carrying bags of cassava – bounce up the bendy tree-ladder, as they probably do every day to get to school.

Life in Africa is frustrating and often disillusioning. Tourists see the romance and glamour of traditional life; they see the wild animals (all in parks now), the exotic dances (posed for their benefit alone in modern African life), the quaintness of traditions and the humour of illogical situations. But when you stay here, become involved in family life in a rural area, amongst the ignorant and prejudiced, it all takes on an edge that is sometimes cruel, often aggressive and jealous. The ‘traditions’ can be barbaric, the uneducated mindset antique, criminal behaviour common, cruel practices all too prevalent.

It’s hard, not very romantic – but then I have made families whom I care for a lot, grandchildren I love, many I respect as they struggle against ignorance and narrow-minded attitudes. It’s both an education and a privilege. It’s tough and it’s warmly loving.

It’s my life now!